Note-Making and Annotation

You ‘take’ notes in class, from SQ3R, and when watching documentaries. You ‘make’ notes when you take that information and turn it into knowledge by manipulating it or changing it into a different set of more purposeful notes (see Revision Techniques). Note-making is a revision technique and it can consist of making cue cards or making mind-maps. When you are assigned an SQ3R scholarly essay to read, you will ‘take’ notes using your Cornell Note-Taking System, but on the essay itself you will ‘make’ notes called annotations.

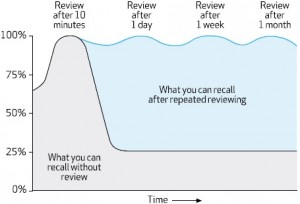

Annotating is not highlighting with a neon pink pen. Underlining may be part of annotating a reading in order to identify a key term or phrase, but it only serves a limited function. Annotation requires you to read and note-take in a reflective manner. After each paragraph, upon reading the last line, you must pause and consider what you have taken notes upon, what you have underlined and comment in your own words what you are thinking in relation to the reading. Thinking about your thinking while reading and note-taking is called metacognition. What you are doing is pausing to reflect upon what you have read and what you have written. By doing so immediately and committing it to writing your chances of retaining this information are increased.

Since you are reading properly (SQ3R) and taking notes (Cornell) you may not think it necessary to annotate. Yet this metacognitive process is extremely powerful since it allows you the pause to reflect and communicate with your mind as to what is significant at that point in the reading. This stream of intercommunication imprints a great deal on your memory, which will be more easily retrieved when you are taking a test or an exam.

How to use your notes

The SQ3R reading method and the Cornell Note Taking system both emphasize frequent review of notes in an iterative manner. Beyond “going over” your notes you will need to be more active in your studying. This is where your revision strategies come into play. As you annotate when you SQ3R and as you reduce and reflect when you take notes you are actively manipulating this information more and more toward your own knowledge. Your notes must be worked with on a daily basis, not merely skimmed, but physically re-written in some form for 20 or 30 minutes in order to retain and improve upon your understanding of course material. This is best done through a variety of revision strategies over a long period of time. Ideally, you should take a semester’s worth of notes from your binder and be able to progressively reduce them down to a powerful pack of portable index cards in the weeks preceding your exam. A well-constructed web diagram on one piece of paper can easily represent a study unit, and so on.

Why specialized vocabulary is important

The most important reason to use the language of the historian is to save you time and effort. Specialized vocabulary, used knowingly and in context, can save you writing several sentences that mean the same thing as a specialized word or a phrase. For each unit under investigation there will be a number of key terms, people, events, and places that represents the knowledge you have gained by taking Cornell Notes in class, using SQ3R on assigned readings, frequently reviewing your notes and using creative revision strategies. Beyond the chapter terms you may wish to work towards progressively incorporating other relevant vocabulary from previous chapters into your most recent work. Since you will be working with primary and secondary sources throughout your history courses it would be a good idea to be conversant with specialized source analysis terms such as ‘provenance’ and ‘reliability’; this not only saves you time and effort but demonstrates through your writing that you are working to exceed the standard in that course.