| Performance Indicators:

P.S ELA-2 Reading Analysis: Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

A. Evaluate the relevant themes and synthesize how they are present in the novel in oral and written responses. P.S ELA-3 Reading Craft and Structure: Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text in which the rhetoric is particularly effective, analyzing how style and content contribute to the power, persuasiveness or beauty of a text. A. Understand SOAPSTone: Speaker, Occasion, Audience, Purpose, Subject, Tone |

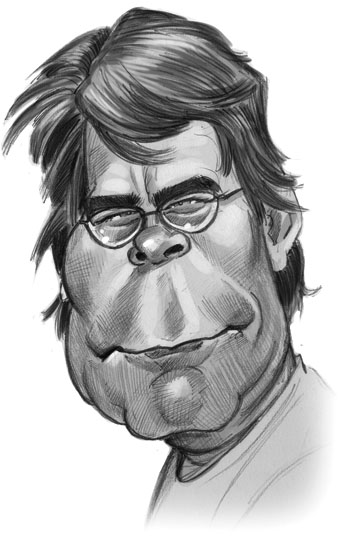

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of the finest guides to writing that you will read. Stephen King uses personnel accounts wrapped in humorist anecdotes to convey meaningful lessons about writing. His memoir is a fantastic blue collared approach to the craft of storytelling. The following excerpt from the book is offered as an essay for our study of nonfiction.

One night— sick to death of Class Reports, Cheerleading Updates, and some lamebrain’s efforts to write a school poem—I created a satiric high school newspaper of my own when I should have been captioning photographs for The Drum.

What resulted was a four-sheet which I called The Village Vomit. The boxed motto in the upper lefthand corner was not “All the News That’s Fit to Print” but “All the Shit That Will Stick.” That piece of dimwit humor got me into the only real trouble of my high school career. It also led me to the most useful writing lesson I ever got.

In typical Mad magazine style (“What, me worry?”), I filled the Vomit with fictional tidbits about the LHS faculty, using teacher nicknames the student body would immediately recognize. Thus Miss Raypach, the study-hall monitor, became Miss Rat Pack; Mr. Ricker, the college-track English teacher (and the school’s most urbane faculty member—he looked quite a bit like Craig Stevens in Peter Gunn), became 51 On Writing Cow Man because his family owned Ricker Dairy; Mr. Diehl, the earth-science teacher, became Old Raw Diehl. As all sophomoric humorists must be, I was totally blown away by my own wit. What a funny fellow I was! A regular mill-town H. L. Mencken! I simply must take the Vomit to school and show all my friends! They would bust a collective gut! As a matter of fact they did bust a collective gut.

This time the trouble was a good deal more serious. Most of the teachers were inclined to be good sports about my teasing—even Old Raw Diehl was willing to let bygones be bygones concerning the pigs’ eyeballs—but one was not. This was Miss Margitan, who taught shorthand and typing to the girls in the business courses. She commanded both respect and fear; in the tradition of teachers from an earlier era, Miss Margitan did not want to be your pal, your psychologist, or your inspiration. She was there to teach business skills, and she wanted all learning to be done by the rules. Her rules. Girls in Miss Margitan’s classes were sometimes asked to kneel on the floor, and if the hems of their skirts didn’t touch the linoleum, they were sent home to change. No amount of tearful begging could soften her, no reasoning could modify her view of the world. Her detention lists were the longest of any teacher in the school, but her girls were routinely selected as valedictorians or salutatorians and usually went on to good jobs. Many came to love her. Others loathed her then and likely still do now, all these years later. These latter girls called her “Maggot” Margitan, as their mothers had no doubt before them. And in The Village Vomit, I had an item which began, “Miss Margitan, known affectionately to Lisbonians everywhere as Maggot . . .” Mr. Higgins, our bald principal (breezily referred to in the Vomit as Old Cue-Ball), told me that Miss Margitan had been very hurt and very upset by what I had written. She was apparently not too hurt to remember that old scriptural admonition which goes “Vengeance is mine,” saith the short-hand teacher, however, Mr. Higgins said she wanted me suspended from school.

In my character, a kind of wildness and a deep conservatism are wound together like hair in a braid. It was the crazy part of me that had first written The Village Vomit and then carried it to school; now that troublesome Mr. Hyde had dubbed up and slunk out the back door. Dr. Jekyll was left to consider how my mom would look at me if she found out I had been suspended—her hurt eyes. I had to put thoughts of her out of my mind, and fast.

I was a sophomore, I was a year older than most others in my class, and at six feet two, I was one of the bigger boys in school. I desperately didn’t want to cry in Mr. Higgins’s office—not with kids surging through the halls and looking curiously in the window at us: Mr. Higgins behind his desk, me in the Bad Boy Seat. In the end, Miss Margitan settled for a formal apology and two weeks of detention for the bad boy who had dared call her Maggot in print. It was bad, but what in high school is not? At the time we’re stuck in it, like hostages locked in a Turkish bath, high school seems the most serious business in the world to just about all of us. It’s not until the second or third class reunion that we start realizing how absurd the whole thing was.