Sports world is still far too homophobic

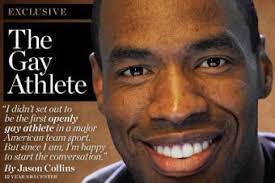

It’s been a week since itinerant and articulate NBA center and former Celtic Jason Collins became the first active professional athlete in one of the four major North American team sports to reveal he was gay. It was a milestone moment, but also a reminder of how far the artificial world of sports is behind the real world in accepting homosexuality.

Collins is out of the closet, but it’s the insular macho culture of major professional sports that needs to come out of the dark and into the light.

Major male professional sports are one of the last — and most visible — places in society where homosexuality is so taboo that, until Collins, its existence couldn’t even be publicly acknowledged. This wasn’t don’t ask, don’t tell. It was just don’t tell or tell a lie to make your teammates and employers feel comfortable.

Sports often have been at the vanguard of or in lockstep with shifting societal attitudes. This was true of race and gender. Now, it’s evolving American cultural mores that are dragging the sports world inexorably toward progress and not the other way around.

Jackie Robinson became the first African-American baseball player in 1947. That was 17 years before the Civil Rights Act was passed. His grace and ability helped dispel and dispute long-held prejudices about African-American capabilities in relation to whites.

As the women’s rights movement gained prominence in the early 1970s, Title IX was put into law in June of 1972, three months after Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment, which shamefully never was ratified by the states as a constitutional amendment.

Title IX wasn’t designed as a sports equality law. It was an educational edict that said no one could be excluded from participation in any educational program or activity on the basis of their sex. But, more than 40 years later, female athletes are the face of Title IX.

With Rhode Island legalizing same-sex marriage last week, there are 10 states in which gay couples legally can marry. The US Supreme Court recently has heard cases that deal with same-sex marriage. Yet, Collins, who was with the Celtics until a Feb. 21 trade to the Washington Wizards that brought Boston Jordan Crawford, is the only known active Big Four professional athlete to publicly identify himself as gay.

If Collins were a banker, a lawyer, or a doctor, his sexual orientation would not be a big deal.

Even if he were a she it would not be as notable.

More than a week before Collins’s announcement, Baylor women’s basketball phenom and WNBA No. 1 pick Brittney Griner identified herself as being a lesbian. It drew a few headlines, but nothing compared with the media maelstrom that followed the Collins revelation in Sports Illustrated.

One of the reasons is that male professional sports are viewed as the epitome of masculinity, one of the last bastions of men being men. Homosexuality is viewed by some in that world as in complete opposition to manly behavior, a violation of guy code.

The 7-foot, 255-pound Collins was more than “man enough” to play for the Celtics.

I think any Celtics fan would say that Boston could have used Collins, a smart, dependable, wily veteran big man, in its series with the Knicks. Coach Doc Rivers, who rued having to ship Collins to Washington, was petrified to play either Chris Wilcox or Shavlik Randolph behind Kevin Garnett.

Because of this dearth of big men in the NBA — not his sexual orientation — the 34-year-old Collins should find a job next season.

Being the first anything is never easy. Collins displayed bravery, conviction, and selflessness in being the first to come out. In the Sports Illustrated story he penned about his decision, Collins said he didn’t do it while with the Celtics because he didn’t want to be a distraction.

He didn’t feel he could mix gay pride and Celtic Pride.

That’s not a commentary on Collins’s internal conflict. It’s a reflection of how out of touch sports are on the issue of homosexuality.

It has been encouraging to see the response to Collins’s announcement from athletes such as Kobe Bryant, who was fined $100,000 by the NBA in 2011 for using a homosexual slur in a rant against an NBA official. And straight athletes such as Brendon Ayanbadejo of the Baltimore Ravens, Chris Kluwe of the Minnesota Vikings, and recently retired linebacker Scott Fujita have been outspoken supporters of gay rights.

But the fact is that professional sports remain a largely homophobic realm of society. Players in multiple sports often sling homosexual slurs at opponents as trash talk. Collins no doubt has had teammates, including in Boston, who have spewed such speech in his presence.

It was just a few months ago back at the Super Bowl that San Francisco 49ers cornerback Chris Culliver sparked controversy by saying in patronizing terms that he would not accept a gay teammate.

“We ain’t got no gay people on the team,” Culliver told radio personality Artie Lange in an interview. “They got to get up out of here if they do. Can’t be with that sweet stuff. Nah, can’t be in the locker room, man.”

It’s easy to vilify Culliver, but he expressed an opinion that is probably more prevalent in private in professional sports than the salutations and well-wishes Collins got in public after his announcement.

People have a right to their opinions and their beliefs. The same goes for athletes. But acceptance and approval are not the same.

Sexual orientation is a personal matter, but that doesn’t mean anyone should be forced to keep their sexual orientation to themselves for fear of professional reprisal.

Sadly, that is still the case in the testosterone-fueled, machismo-filled world of professional sports.

Sports aren’t taking the lead this time on social equality. They’re far behind.

It’s time to start playing catch-up.

Christopher L. Gasper can be reached at cgasper@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @cgasper.