The following essays appear on this page:

Sending Grandma to the Ovens

by Colin Cohen

A Modest Proposal

By Jonathan Swift (1729)

Kadish for Zelig

by Solly Ganor

The Ring of Time

E. B. White

The Death of the Moth (1942)

Virginia Woolf

The Scotty Who Knew Too Much

by James Thurber

A Child’s Christmas in Wales

by Dylan Thomas

Advice to Youth

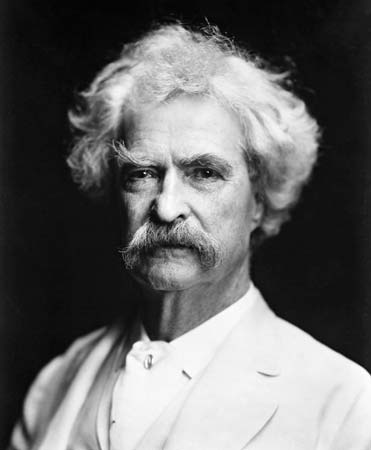

by Mark Twain

Of the Passing of the First-Born

by W.E.B. Du Bois

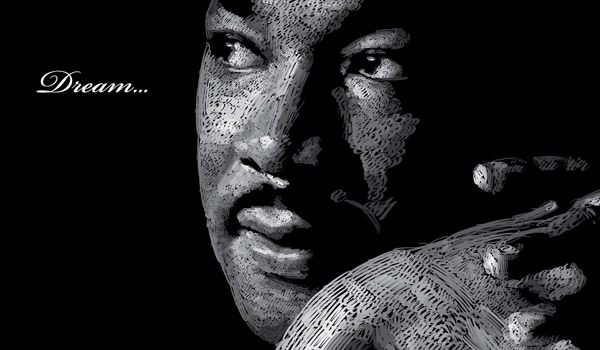

I Have a Dream

by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Thinking as a Hobby

by William Golding

A Slander

BY ANTON CHEKHOV

SENDING GRANDMA TO THE OVENS

by Colin Cohen

As our nation gets older and older, we will soon face a major dilemma: what will we do when the vast majority of our citizenry is composed of non-productive senior citizens, who instead of contributing to our country’s wealth are draining it of its very sustenance? The answer lies in providing these people a special form of early retirement: extermination. While this may seem a bit harsh, it will create unmatched economic prosperity and will relieve the heavy emotional burden carried by families who must support — and even occasionally visit — their elderly members.

Natural law, a law clearly inspired by God that preceded and should supersede all man-made laws, has a special method for dealing with the elderly, a method that applies to all species: either they are to be eaten by younger, stronger, and faster members of other species; or, realizing their innate uselessness, they leave the tribe and go off alone where they can peacefully starve to death and be eaten by vultures. In the beginning, this law applied to humans as well — it only deviated when man adopted Confucian and Judeo-Christian philosophy, which mistakenly taught reverence for the old.

Still, up until the past century, the burden of this reverence was placed solely on the family; and even then, it was purely voluntary. If a family couldn’t afford (or couldn’t be troubled) to take care of their elderly, the hardship didn’t fall on society. In fact, as these people were forced to work up until their deaths in workhouses or on the street (and ate many tins of cat food), they actually contributed to society, albeit in a small and somewhat unsightly way.

This symbiotic system unfortunately ended with the Marxian-laced policies of the New Deal. Just because of a little depression and a few million hungry old people, Franklin Roosevelt autocratically encumbered future generations with an evil program called Social Security. With Social Security, society was now legally bound to financially support the elderly. And while, in theory, the costs were to be financed by individual contributions, by linking payments made by Social Security — however small — to the cost of living, they created the possibility of an endless pit.

Things got much worse in the 1960s when Lyndon Johnson and his Great Society gave us Medicare, which guaranteed medical insurance for the elderly. It was no longer sufficient to help them pay for their cat food, now we would have to pay for some of their medical expenses too. This program, in combination with Social Security, also had the undesirable effect of raising life expectancy dramatically, raising costs even higher.

The situation was even further exasperated with the formation of the American Association of Retired People (AARP), a political action committee created to protect and enhance government-sponsored handouts to the elderly. This group is now one of the strongest and most influential PACs — all due to the insignificant fact that old people, because they have nothing better to do, actually vote.

The economic consequences of abandoning God’s natural law is enormous and will only worsen exponentially. Currently, the cost for Medicare is 220 billion dollars per year. By 2011, this cost is estimated to increase to 491 billion dollars, or 19 percent of the federal budget. The cost will then soon double when the Baby Boom generation begins to retire.

As a much larger percent of the population will be elderly — the US Census estimates that by 2025 the population over 65 will increase 80 percent while the number of working Americans will increase only 15 percent — payroll and other federal taxes will have to increase dramatically to meet the costs. And the Congressional Budget Office says that by 2030, the cost of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security will consume 75 percent of the federal budget. In the worse case, we could be facing the insolvency of the entire government; and in the very best scenario, it will mean far less money for much more needed government programs, such as building weapons of mass destruction.

Additionally, these costs do not include the many long-term care costs that are not covered by the federal government, such as lengthy nursing homes stays, which in general are paid mostly by families. Today, a year of nursing home costs on average $50,000. In future, as these costs double, triple, or even quadruple, many families will face certain ruin. At the very least, they will be unable to afford satellite television.

The elderly problem has also created a hidden cost: the cost of health care insurance in general. The ever-rising cost of health insurance, which has become unaffordable for many working people, is directly related to the ever-rising cost of providing health care, which the elderly receive at an extremely disproportional rate to the public at large.

Of course, money isn’t everything. The care of the elderly carries many emotional costs. For families that can afford external care, they must give up part of their hard-earned weekends and holidays to visit elderly members. Men must forgo time on the golf course, women time at the salon, and children time in front of the TV watching cartoons or playing video games — all to visit depressing, urine-soaked institutions of impending death. And how many of these old people truly appreciate the minutes their families sacrifice when they come and visit?

An even worse situation is when families can’t afford external care or when their elderly relatives selfishly refuse such care. They must then suffer and patronize them in their own homes, cook and clean for them, and listen to their useless babble. And the old people, as they become more and more incoherent with age, soon become an embarrassment — a consequence of which is that families must curtail dinner and cocktail parties, which could have a major effect on their social standing within the community.

Of course, identifying problems is sometimes much simpler than identifying solutions. One method for determining solutions to problems facing our society, though, is to look toward corporate America. Often solutions developed by large businesses can be applied to government. When companies become bloated and need to reduce costs — so as to ensure shareholder profits and executive bonuses — a relatively painless solution is to implement an early retirement program, where employees are encouraged to retire prematurely by offering them financial incentives.

Based on this model, I propose we develop a special early retirement program as a final solution to the problem of the elderly. The program will offer the elderly and their families certain financial incentives in exchange for their extermination. Unlike most corporate early retirement programs, though, this program will not be voluntary.

The program will work as follows: everyone 65 or older will report — or will be brought forcibly if necessary — to their local termination center, which will be conveniently located across the country in local shopping malls. At this time — if they report on their own volition — they will receive one-half of their total contribution to the Social Security system, which is still far more than what they would have received through the current system. They can either leave this money to their descendants or donate it to charity. The choice is theirs. After completing their paperwork, the elderly will be transported to crematories for further processing.

Undoubtedly, this program will be a little controversial. Some seniors, acting purely out of self-interest, might complain; and as the AARP has a stranglehold on many politicians, it might be difficult to get Congress to approve it. Fortunately, Section 501 of the Defense Security Enhancement Act, also known as Patriot II, provides the executive branch the much needed ability to presumptively denationalize American citizens who support the activities of any organization that it has deemed terrorist. As “terrorism” can be defined as the “systematic use of intimidation to coerce governments,” the AARP could easily be branded a terrorist organization by the president; and hence all of its members — which include almost the entire elderly population — could be legally expatriated. And if the Supreme Court attempts to overrule this interpretation, it too can be deemed “terrorist.”

The families of seniors may also protest, as many mistakenly believe that they actually love their elder members. This can be resolved through a concerted plan of reeducation in combination with television and billboard advertising. If we get a few sport stars and entertainers onboard, the nation’s undeniably pliable will will soon change. Especially when the checks for dead relatives start coming in the mail.

Once the early retirement program is in place, the direct economic benefits of it will be staggering. Firstly, those entering the workforce will no longer have to donate a large chunk of their paycheck to Social Security — allowing them to use the money far more wisely on such things as booze, drugs, sex, and lottery tickets. Secondly, as the federal government will no longer have to prop up Social Security and Medicare, it can channel all these funds to the military, who can then implement early retirement programs across the world. Thirdly, health care costs will plummet, allowing hospitals, physicians, and insurance companies to earn far more money. Fourthly, families will no longer have to bear the economic and emotional costs of long-term care, freeing both disposable income and the opportunity to waste it. Additionally, by ending long-term care, we could convert all the nursing homes into luxury condominiums. Finally, this program will provide thousands of minimum wage jobs to those undereducated minorities who will work in the crematories.

The program can also produce an important indirect economic benefit. As the human body is rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, the ashes of our seniors will make excellent fertilizer, which we can provide to our farmers at low cost, who in turn will use it to grow tasty grains, fruits, and vegetables for us to enjoy. We can also export the fertilizer to poor Third World nations, through loans provided by the IMF at marginally usurious interest rates, so they too can enjoy our dead elderly. And through USAID and the Peace Corps, we can even teach these wretches how to make their own fertilizer.

Early retirement will also provide a host of side benefits. The roads and supermarket lines will move quicker, children will no longer be indoctrinated with old-fashioned morals and values, and there will be no more Dick Clark specials on TV. We will also need far fewer election workers; for by eliminating senior citizens, we will eliminate the majority of voters. Who knows, perhaps we could even eliminate voting all together.

The extermination of the elderly, true to both natural law and economic order, will provide a plethora of benefits, without any discernible drawbacks. America, send your grandfathers and grandmothers to the ovens — if not for your greed, than for the greed of the nation.

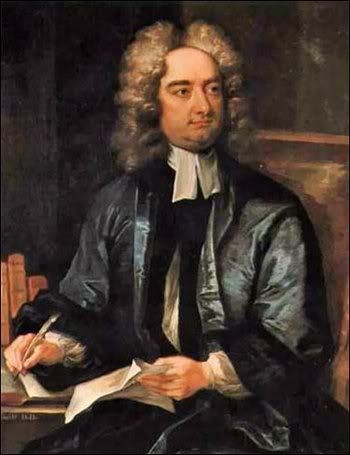

A Modest Proposal

By Jonathan Swift (1729)

For Preventing The Children of Poor People in Ireland

From Being Aburden to Their Parents or Country, and

For Making Them Beneficial to The Public

It is a melancholy object to those who walk through this great town or travel in the country, when they see the streets, the roads, and cabin doors, crowded with beggars of the female sex, followed by three, four, or six children, all in rags and importuning every passenger for an alms. These mothers, instead of being able to work for their honest livelihood, are forced to employ all their time in strolling to beg sustenance for their helpless infants: who as they grow up either turn thieves for want of work, or leave their dear native country to fight for the Pretender in Spain, or sell themselves to the Barbadoes.

I think it is agreed by all parties that this prodigious number of children in the arms, or on the backs, or at the heels of their mothers, and frequently of their fathers, is in the present deplorable state of the kingdom a very great additional grievance; and, therefore, whoever could find out a fair, cheap, and easy method of making these children sound, useful members of the commonwealth, would deserve so well of the public as to have his statue set up for a preserver of the nation.

But my intention is very far from being confined to provide only for the children of professed beggars; it is of a much greater extent, and shall take in the whole number of infants at a certain age who are born of parents in effect as little able to support them as those who demand our charity in the streets.

”I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled …”

As to my own part, having turned my thoughts for many years upon this important subject, and maturely weighed the several schemes of other projectors, I have always found them grossly mistaken in the computation. It is true, a child just dropped from its dam may be supported by her milk for a solar year, with little other nourishment; at most not above the value of 2s., which the mother may certainly get, or the value in scraps, by her lawful occupation of begging; and it is exactly at one year old that I propose to provide for them in such a manner as instead of being a charge upon their parents or the parish, or wanting food and raiment for the rest of their lives, they shall on the contrary contribute to the feeding, and partly to the clothing, of many thousands.

There is likewise another great advantage in my scheme, that it will prevent those voluntary abortions, and that horrid practice of women murdering their bastard children, alas! too frequent among us! sacrificing the poor innocent babes I doubt more to avoid the expense than the shame, which would move tears and pity in the most savage and inhuman breast.

The number of souls in this kingdom being usually reckoned one million and a half, of these I calculate there may be about two hundred thousand couple whose wives are breeders; from which number I subtract thirty thousand couples who are able to maintain their own children, although I apprehend there cannot be so many, under the present distresses of the kingdom; but this being granted, there will remain an hundred and seventy thousand breeders. I again subtract fifty thousand for those women who miscarry, or whose children die by accident or disease within the year. There only remains one hundred and twenty thousand children of poor parents annually born. The question therefore is, how this number shall be reared and provided for, which, as I have already said, under the present situation of affairs, is utterly impossible by all the methods hitherto proposed. For we can neither employ them in handicraft or agriculture; we neither build houses (I mean in the country) nor cultivate land: they can very seldom pick up a livelihood by stealing, till they arrive at six years old, except where they are of towardly parts, although I confess they learn the rudiments much earlier, during which time, they can however be properly looked upon only as probationers, as I have been informed by a principal gentleman in the county of Cavan, who protested to me that he never knew above one or two instances under the age of six, even in a part of the kingdom so renowned for the quickest proficiency in that art.

I am assured by our merchants, that a boy or a girl before twelve years old is no salable commodity; and even when they come to this age they will not yield above three pounds, or three pounds and half-a-crown at most on the exchange; which cannot turn to account either to the parents or kingdom, the charge of nutriment and rags having been at least four times that value.

I shall now therefore humbly propose my own thoughts, which I hope will not be liable to the least objection.

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout.

I do therefore humbly offer it to public consideration that of the hundred and twenty thousand children already computed, twenty thousand may be reserved for breed, whereof only one-fourth part to be males; which is more than we allow to sheep, black cattle or swine; and my reason is, that these children are seldom the fruits of marriage, a circumstance not much regarded by our savages, therefore one male will be sufficient to serve four females. That the remaining hundred thousand may, at a year old, be offered in the sale to the persons of quality and fortune through the kingdom; always advising the mother to let them suck plentifully in the last month, so as to render them plump and fat for a good table. A child will make two dishes at an entertainment for friends; and when the family dines alone, the fore or hind quarter will make a reasonable dish, and seasoned with a little pepper or salt will be very good boiled on the fourth day, especially in winter.

I have reckoned upon a medium that a child just born will weigh 12 pounds, and in a solar year, if tolerably nursed, increaseth to 28 pounds.

I grant this food will be somewhat dear, and therefore very proper for landlords, who, as they have already devoured most of the parents, seem to have the best title to the children.

Infant’s flesh will be in season throughout the year, but more plentiful in March, and a little before and after; for we are told by a grave author, an eminent French physician, that fish being a prolific diet, there are more children born in Roman Catholic countries about nine months after Lent than at any other season; therefore, reckoning a year after Lent, the markets will be more glutted than usual, because the number of popish infants is at least three to one in this kingdom: and therefore it will have one other collateral advantage, by lessening the number of papists among us.

I have already computed the charge of nursing a beggar’s child (in which list I reckon all cottagers, laborers, and four-fifths of the farmers) to be about two shillings per annum, rags included; and I believe no gentleman would repine to give ten shillings for the carcass of a good fat child, which, as I have said, will make four dishes of excellent nutritive meat, when he hath only some particular friend or his own family to dine with him. Thus the squire will learn to be a good landlord, and grow popular among his tenants; the mother will have eight shillings net profit, and be fit for work till she produces another child.

Those who are more thrifty (as I must confess the times require) may flay the carcass; the skin of which artificially dressed will make admirable gloves for ladies, and summer boots for fine gentlemen.

As to our city of Dublin, shambles may be appointed for this purpose in the most convenient parts of it, and butchers we may be assured will not be wanting; although I rather recommend buying the children alive, and dressing them hot from the knife, as we do roasting pigs.

A very worthy person, a true lover of his country, and whose virtues I highly esteem, was lately pleased in discoursing on this matter to offer a refinement upon my scheme. He said that many gentlemen of this kingdom, having of late destroyed their deer, he conceived that the want of venison might be well supplied by the bodies of young lads and maidens, not exceeding fourteen years of age nor under twelve; so great a number of both sexes in every country being now ready to starve for want of work and service; and these to be disposed of by their parents, if alive, or otherwise by their nearest relations. But with due deference to so excellent a friend and so deserving a patriot, I cannot be altogether in his sentiments; for as to the males, my American acquaintance assured me, from frequent experience, that their flesh was generally tough and lean, like that of our schoolboys by continual exercise, and their taste disagreeable; and to fatten them would not answer the charge. Then as to the females, it would, I think, with humble submission be a loss to the public, because they soon would become breeders themselves; and besides, it is not improbable that some scrupulous people might be apt to censure such a practice (although indeed very unjustly), as a little bordering upon cruelty; which, I confess, hath always been with me the strongest objection against any project, however so well intended.

But in order to justify my friend, he confessed that this expedient was put into his head by the famous Psalmanazar, a native of the island Formosa, who came from thence to London above twenty years ago, and in conversation told my friend, that in his country when any young person happened to be put to death, the executioner sold the carcass to persons of quality as a prime dainty; and that in his time the body of a plump girl of fifteen, who was crucified for an attempt to poison the emperor, was sold to his imperial majesty’s prime minister of state, and other great mandarins of the court, in joints from the gibbet, at four hundred crowns. Neither indeed can I deny, that if the same use were made of several plump young girls in this town, who without one single groat to their fortunes cannot stir abroad without a chair, and appear at playhouse and assemblies in foreign fineries which they never will pay for, the kingdom would not be the worse.

Some persons of a desponding spirit are in great concern about that vast number of poor people, who are aged, diseased, or maimed, and I have been desired to employ my thoughts what course may be taken to ease the nation of so grievous an encumbrance. But I am not in the least pain upon that matter, because it is very well known that they are every day dying and rotting by cold and famine, and filth and vermin, as fast as can be reasonably expected. And as to the young laborers, they are now in as hopeful a condition; they cannot get work, and consequently pine away for want of nourishment, to a degree that if at any time they are accidentally hired to common labor, they have not strength to perform it; and thus the country and themselves are happily delivered from the evils to come.

I have too long digressed, and therefore shall return to my subject. I think the advantages by the proposal which I have made are obvious and many, as well as of the highest importance.

For first, as I have already observed, it would greatly lessen the number of papists, with whom we are yearly overrun, being the principal breeders of the nation as well as our most dangerous enemies; and who stay at home on purpose with a design to deliver the kingdom to the Pretender, hoping to take their advantage by the absence of so many good protestants, who have chosen rather to leave their country than stay at home and pay tithes against their conscience to an episcopal curate.

Secondly, The poorer tenants will have something valuable of their own, which by law may be made liable to distress and help to pay their landlord’s rent, their corn and cattle being already seized, and money a thing unknown.

Thirdly, Whereas the maintenance of an hundred thousand children, from two years old and upward, cannot be computed at less than ten shillings a-piece per annum, the nation’s stock will be thereby increased fifty thousand pounds per annum, beside the profit of a new dish introduced to the tables of all gentlemen of fortune in the kingdom who have any refinement in taste. And the money will circulate among ourselves, the goods being entirely of our own growth and manufacture.

Fourthly, The constant breeders, beside the gain of eight shillings sterling per annum by the sale of their children, will be rid of the charge of maintaining them after the first year.

Fifthly, This food would likewise bring great custom to taverns; where the vintners will certainly be so prudent as to procure the best receipts for dressing it to perfection, and consequently have their houses frequented by all the fine gentlemen, who justly value themselves upon their knowledge in good eating: and a skilful cook, who understands how to oblige his guests, will contrive to make it as expensive as they please.

Sixthly, This would be a great inducement to marriage, which all wise nations have either encouraged by rewards or enforced by laws and penalties. It would increase the care and tenderness of mothers toward their children, when they were sure of a settlement for life to the poor babes, provided in some sort by the public, to their annual profit instead of expense. We should see an honest emulation among the married women, which of them could bring the fattest child to the market. Men would become as fond of their wives during the time of their pregnancy as they are now of their mares in foal, their cows in calf, their sows when they are ready to farrow; nor offer to beat or kick them (as is too frequent a practice) for fear of a miscarriage.

Many other advantages might be enumerated. For instance, the addition of some thousand carcasses in our exportation of barreled beef, the propagation of swine’s flesh, and improvement in the art of making good bacon, so much wanted among us by the great destruction of pigs, too frequent at our tables; which are no way comparable in taste or magnificence to a well-grown, fat, yearling child, which roasted whole will make a considerable figure at a lord mayor’s feast or any other public entertainment. But this and many others I omit, being studious of brevity.

Supposing that one thousand families in this city, would be constant customers for infants flesh, besides others who might have it at merry meetings, particularly at weddings and christenings, I compute that Dublin would take off annually about twenty thousand carcasses; and the rest of the kingdom (where probably they will be sold somewhat cheaper) the remaining eighty thousand.

I can think of no one objection, that will possibly be raised against this proposal, unless it should be urged, that the number of people will be thereby much lessened in the kingdom. This I freely own, and ’twas indeed one principal design in offering it to the world. I desire the reader will observe, that I calculate my remedy for this one individual Kingdom of Ireland, and for no other that ever was, is, or, I think, ever can be upon Earth. Therefore let no man talk to me of other expedients: Of taxing our absentees at five shillings a pound: Of using neither cloaths, nor houshold furniture, except what is of our own growth and manufacture: Of utterly rejecting the materials and instruments that promote foreign luxury: Of curing the expensiveness of pride, vanity, idleness, and gaming in our women: Of introducing a vein of parsimony, prudence and temperance: Of learning to love our country, wherein we differ even from Laplanders, and the inhabitants of Topinamboo: Of quitting our animosities and factions, nor acting any longer like the Jews, who were murdering one another at the very moment their city was taken: Of being a little cautious not to sell our country and consciences for nothing: Of teaching landlords to have at least one degree of mercy towards their tenants. Lastly, of putting a spirit of honesty, industry, and skill into our shop-keepers, who, if a resolution could now be taken to buy only our native goods, would immediately unite to cheat and exact upon us in the price, the measure, and the goodness, nor could ever yet be brought to make one fair proposal of just dealing, though often and earnestly invited to it.

Therefore I repeat, let no man talk to me of these and the like expedients, ’till he hath at least some glympse of hope, that there will ever be some hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.

But, as to my self, having been wearied out for many years with offering vain, idle, visionary thoughts, and at length utterly despairing of success, I fortunately fell upon this proposal, which, as it is wholly new, so it hath something solid and real, of no expence and little trouble, full in our own power, and whereby we can incur no danger in disobliging England. For this kind of commodity will not bear exportation, and flesh being of too tender a consistence, to admit a long continuance in salt, although perhaps I could name a country, which would be glad to eat up our whole nation without it.

After all, I am not so violently bent upon my own opinion as to reject any offer proposed by wise men, which shall be found equally innocent, cheap, easy, and effectual. But before something of that kind shall be advanced in contradiction to my scheme, and offering a better, I desire the author or authors will be pleased maturely to consider two points. First, as things now stand, how they will be able to find food and raiment for an hundred thousand useless mouths and backs. And secondly, there being a round million of creatures in human figure throughout this kingdom, whose whole subsistence put into a common stock would leave them in debt two millions of pounds sterling, adding those who are beggars by profession to the bulk of farmers, cottagers, and laborers, with their wives and children who are beggars in effect: I desire those politicians who dislike my overture, and may perhaps be so bold as to attempt an answer, that they will first ask the parents of these mortals, whether they would not at this day think it a great happiness to have been sold for food, at a year old in the manner I prescribe, and thereby have avoided such a perpetual scene of misfortunes as they have since gone through by the oppression of landlords, the impossibility of paying rent without money or trade, the want of common sustenance, with neither house nor clothes to cover them from the inclemencies of the weather, and the most inevitable prospect of entailing the like or greater miseries upon their breed for ever.

I profess, in the sincerity of my heart, that I have not the least personal interest in endeavoring to promote this necessary work, having no other motive than the public good of my country, by advancing our trade, providing for infants, relieving the poor, and giving some pleasure to the rich. I have no children by which I can propose to get a single penny; the youngest being nine years old, and my wife past child-bearing.

The End

Kadish for Zelig

by Solly Ganor

If I needed a reminder why many Holocaust survivors live in Israel and cling to it with heart and soul, despite the endless wars and the suicide bombings, this recent journey supplied us with the answer. The flight from Tel Aviv to Munich lasts less than four hours, but my memory takes me back fifty seven years, when I was a teenage slave laborer for the Nazis in one of the outer camps of Dachau. Towards the end of the war, they were so desperately in need of labor that the Nazis reluctantly gave up the idea of gassing all Jews, irrespective of their gender or age. They continued to gas women with children and old people, but those whom they considered still capable of work, were temporarily spared. They even coined a phrase for those of us: “Vernichtung durch Arbeit”–”Annihilation through Work.” In fact, they starved us and made us work twelve hours a day at hard labor, condemning us to a slow agonizing death.

There were in all eleven outer camps of Dachau, where in nine months more than fifteen thousand Jewish slaves, out of a total of thirty thousand, died of starvation, hard labor and beatings by the German supervisors and the SS guards. I was in an outer camp of Dachau, known as Lager X (Camp 10), near Utting, a picturesque little town by the Amersee. Before the war writers and artists used to live there. I was told that the famous Kurt Weil lived there before Hitler came to power.

In July 1944, with the Soviet troops approaching the Kovno ghetto where I was imprisoned for three years, the Nazis transported us halfway across Europe to Bavaria. There, near the medieval town of Landsberg and surroundings, Hitler decided in the last phases of the war to build gigantic underground factories where the jet fighter Messerschmidt ME262 was to be built. This was Hitler’s promised secret weapon that would sweep the American and British planes out of the German skies.

We, the half-starved Jews of Lithuania, Poland, and Hungary were to build these gigantic factories, and perish while building it.

The construction sight was called Moll, named after the owner of the building company, Leonard Moll. I will never forget the day when I first laid eyes on it. We were driving from Utting in a truck, to deliver a load of potatoes. In our camp, it was known that the Germans were building some kind of underground factory, and we heard terrible stories about it. We traveled for what seemed like an hour along a tree-lined dirt road. Darkness had fallen, and in the distance we could hear the low grinding roar of heavy machinery.

The din increased just before we emerged into a huge clearing lit by the glare of floodlights. The road dropped into a vast excavation, and from it rose an enormous concrete vault, bristling with vertical reinforcing rods so that it looked like some monstrous hedgehog. Narrow railroad tracks curved towards the opening.

The installation was a half-cylinder of concrete, 1,300 feet long and spanning more than 275 feet at the base. It rose some 95 feet into the air at the top of the arch. Under the glaring lights, cranes and bulldozers moved into and around its mouth. Scores of tractors, trucks, and other heavy equipment created an ear-shattering roar. Along the sides, scores of prisoners stood on platforms handling huge flexible hoses that spewed wet cement into the spiked grid work, while others moved about with shovels and buckets. Everywhere we looked we saw what looked like thousands of men in striped uniforms moving about the compound, carrying lumber, iron rods and sacks of cement.

It was like an enormous, evil hive. Even as we watched, we heard inhuman screams coming from above. The men who were maneuvering the huge hose had lost their grip, and the pipe began writhing about, spewing concrete in all directions. The men desperately tried to seize it, but it whipped and flailed and knocked several men off their feet. One after another they fell screaming onto the spikes, while the hose poured hundreds of pounds of concrete on top of them. The scene I described took place towards the end of 1944.

The men I saw fall into the concrete are still entombed in its massive construction to this day. Among the men who slaved on this project was my childhood friends Uri Chanoch and Chaim Konwitz, Avraham Fein, Monchik Levin, and many others. Fifty-eight years later we had returned to “Moll” to say Kadish for these men.

One of the men entombed I knew personally. His name was Zelig. I never found out his last name, but I knew he was from a small town in Lithuania. He was one of the “human horses” who were engaged in pulling a food cart from the village of Utting to a German worker’s kitchen. I too was a horse, and in all we were four teenagers who were given that job.

The German kitchen was near the site where we were slaving at hard labor, a place known as Dyckerhof and Wydman. (Dyckerhof and Wydman, by the way, is one of the largest construction companies in Germany today.) At that stage of the war, gasoline became a very precious commodity, and we the Jewish slaves, were used as ‘horses’. Make no mistake, being a “horse” was a coveted job in the camp, the alternative was to carry hundred pounds of cement on your back, or iron rails to build tracks for the trolleys. There was another advantage in being a “horse” the cart we were pulling was filled with

food for the kitchen, and we always managed to scrounge a crust of bread or a bowl of soup in Utting.

Zelig was an ardent Zionist and always talked about how he would work the land of Israel if he ever survived the war. “If I will ever survive this hell and get to the land of Israel, I will kiss every grain of sand, and work twenty four hour a day to build it up,” he would say, and he would say it with so much longing in his voice that it had an effect on all of us.

But his wish never came true. He fell into the roof of “Moll” and became entombed with the others, by sheer mistake, and I was there to see him fall. I will never forget his screams as he fell to his horrible death. Fifty-eight years later we stood quietly reciting Kadish for the dead and I spoke to Zelig of the land of Israel that he loved so much, and like Moses, never got to see it.

Yes, Zelig, I want to tell you of the true miracle of Israel, that puts to shame the miracles of the Bible. Yes, Zelig, I survived and saw your beloved land. I still remember the mountains of Carmel rising from the morning mist, as our ship approached Haifa.

We were a ship full of penniless Holocaust survivors, and we all sang (what was later to become our National Anthem) the Hatikvah (the Hope) with tears in our eyes. No sooner had we landed on its shore, as we were called to defend the newly proclaimed land of Israel. Five Arab armies descended on us trying to strangle us at our birth.

I will never forget the moment when I was given a rifle and was told by my commanding officer: “This is your land now, defend it with all you have got, for you will never have another chance to have your own country.”

And defend it we did, Zelig. Many of us died, some of them the last sons of once glorious Jewish families of Europe, but they died for the only cause worth while fighting for. I was only sorry, Zelig, that you couldn’t be there by my side fighting for the land you loved so much. With the onslaught of the combined Arab armies, the world gave us a week to survive and what is more, no one lifted a finger to help us. The Arabs were to finish what Hitler had started.

So what else is new? But the world didn’t reckon with one small thing, Zelig. We were not the defenseless Jews anymore. We were now back in our homeland fighting for the resurrected State of Israel. Against all odds we won the war, and set out to prepare the ground for another million penniless refugees. Jews, who escaped with their lives from the Arabic countries, where they were robbed of their properties, possessions and money.

And soon another million arrived from all over the world, and another million, from Poland and the Baltics.

From six hundred thousand in 1948, we grew into a population of two and half million within a few years of the creation of the State. Ironically, when the Jewish Agency asked for seventy-five thousands certificates to save some Jews from Hitler’s gas chambers, the British claimed that the country couldn’t absorb such a vast number of Jews. That was the infamous White Paper.

The fledgling state soon ran out of money to buy the basic needs for the swelling population. We lived in tents and ate what the small agricultural settlements could provide us with. It wasn’t enough, but we weren’t starving.

Very soon, we began to build a healthy democratic society, creating wealth by our brains and hard work, as the country had no natural resources. Soon Jews from over fifty countries full of enthusiasm came to help build the State of Israel. Our population grew even more, and despite the predictions of international experts, that no country can absorb so many millions without an economical collapse, Israel continued to develop in every field. The Jews, who hadn’t tilled the land for two thousands years became experts in agriculture, achieving internationally unprecedented results.

Ironically, the stereotyped Jew, the merchant, the so-called money lender, the usurer, went all over the world to teach agriculture and know-how in many fields. What is even more ironic, we became experts in warfare. “The people of the book,” as we were known for two thousand years, soft and cowardly, as proclaimed by the anti-Semites, soon learned to become experts in that field as well. The fact is that in 1967, we stunned the world by defeating the combined Arab armies in six days.

The Arab countries, unwilling to accept their defeat in the battlefield, and unwilling to accept us in their midst, launched war after war, trying to eliminate the State of Israel. Every time they suffered crushing defeats, despite their superior numbers and new-technology weapons the Soviets supplied them with.

Today we are a modern society of six million people. The country that once was a mosquito-infested swamp land, or dry desert land, blossomed into a modern society of six million people. From nothing, we created a land that not only boasts of the highest standards in every field of achievement, but also developed one of the highest high-tech industries in the world. We export per capita in dollars more than any other country in the world. And we did it all with hard work, brains, and guts.

Yes, Zelig, I always admired you for your love of that distant land called Eretz Israel. I never believed that I could have such emotions for any land. Today, after having fought for it in four bloody wars, and after spending a lifetime in helping rebuild it, I can finally say that I do share your feelings for the land of Israel. Yes, Zelig, you can be proud of us. We, the survivors of the Holocaust, have risen from the ashes of Europe and helped create the miracle of Israel.

Never again will they line us up defenseless before the gas chambers of Europe!

Rest in peace, my friend Zelig, rest in peace.

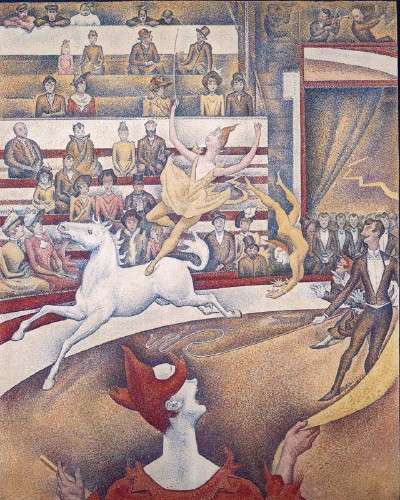

The Ring of Time

E. B. White, author of Charlotte’s Web

After the lions had returned to their cages, creeping angrily through the chutes, a little bunch of us drifted away and into an open doorway nearby, where we stood for a while in semi-darkness watching a big brown circus horse go harumphing around the practice ring. His trainer was a woman of about forty, and the two of them, horse and woman, seemed caught up in one of those desultory treadmills of afternoon from which there is no apparent escape. The day was hot, and we kibitzers were grateful to be briefly out of the sun’s glare. The long rein, or tape, by which the woman guided her charge counterclockwise in his dull career formed the radius of their private circle, of which she was the revolving center; and she, too, stepped in a tiny circumference of her own, in order to accommodate the horse and allow him his maximum scope. She had on a short-skirted costume and conical straw hat. Her legs were bare and she wore high heels, which probed deep into the loose tanbark and kept her ankles in a state of constant turmoil. The great size and meekness of the horse, the repetitious exercise, the heat of the afternoon, all exerted a hypnotic charm that invited boredom; we spectators were experiencing a languor—we neither expected relief nor felt entitled to any. We had paid a dollar to get into the grounds, to be sure, but we had got our dollar’s worth a few minutes before, when the lion tamer’s whiplash had got caught around a toe of one of the lions. What more did we want for a dollar?

Behind me I heard someone say, “Excuse me, please,” in a low voice. She was halfway into the building when I turned and saw her—a girl of sixteen or seventeen, politely threading her way through us onlookers who blocked the entrance. As she emerged in front of us, I saw that she was barefoot, her dirty little feet fighting the uneven ground. In most respects she was like any of the two or three dozen showgirls you encounter if you wander about the winter quarters of Mr. John Ringling North’s circus, in Sarasota—cleverly proportioned, deeply browned by the sun, dusty, eager, and almost naked. But her grave face and the naturalness of her manner gave her a sort of quick distinction and brought a new note into the gloomy octagonal building where we had all cast our lot for a few moments. As soon as she had squeezed through the crowd, she spoke a word or two to the older woman, whom I took to be her mother, stepped into the ring, and waited while the horse coasted to a stop in front of her. She gave the animal a couple of affectionate swipes on his enormous neck and then swung herself aboard. The horse immediately resumed his rocking canter, the woman goaded him on, chanting something that sounded like, “Hop! Hop!”

In attempting to recapture this mild spectacle, I am merely acting as a recording secretary for one of the oldest societies—the society of those who, at one time or another, have surrendered, without even a show of resistance, to the bedazzlement of a circus rider. As a writing man, or secretary, I have always felt charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even a small one were to be lost. But it is not easy to communicate anything of this nature. The circus comes as close to being the world in a microcosm as anything I know; in a way, it puts all the rest of show business in the shade. Its magic is universal and complex. Out of its wild disorder comes order; from its rank smell rises the good aroma of courage and daring; out of its preliminary shabbiness comes the final splendor. And buried in the familiar boast of its advance agents lies the modesty of most of its people. For me the circus is at its best before it has been put together. It is at its best at certain moments when it comes to a point, as though a burning glass, in the activity and destiny of a single performer out of so many. One ring is always bigger than three. One rider, one aerialist, is always greater than six. In short, a man has to catch the circus unawares to experience its full impact and share its gaudy dream.

The ten-minute ride the girl took achieved—as far as I was concerned, who wasn’t looking for it, and quite unbeknownst to her, who wasn’t even striving for it—the thing that is sought by performers everywhere, on whatever stage, whether struggling in the tidal currents of Shakespeare or bucking the difficult motion of a horse. I somehow got the idea she was just cadging a ride, improving a shining ten minutes in the diligent way all serious artists seize free moments to hone the blade of their talent and keep themselves in trim. Her brief tour included only elementary postures and tricks, perhaps because they were all she was capable of, perhaps because her warm-up at this hour was unscheduled and the ring was not rigged for a real practice session. She swung herself off and on the horse several times, gripping his mane. She did a few knee-stands—or whatever they are called—dropping to her knees and quickly bouncing back up on her feet again. Most of the time she simply rode in a standing position, well aft on the breast, her hands hanging easily at her sides, her head erect, her straw-colored ponytail lightly brushing her shoulders, the blood of exertion showing faintly through the tan of her skin. Twice she managed a one-foot stance—a sort of ballet pose, with arms outstretched. At one point the neck strap of her bathing suit broke and she went twice around the ring in the classic attitude of a woman making minor repairs to a garment. The fact that she was standing on the back of a horse while doing this invested the matter with a clownish significance that perfectly fitted the spirit of the circus—jocund, yet charming. She just rolled the strap into a neat ball and stowed it inside her bodice while the horse rocked and rolled beneath her in dutiful innocence. The bathing suit proved as self-reliant as its owner and stood up well enough without benefit of a strap.

The richness of the scene was in its plainness, its natural condition—of horse, of ring, of girl, even to the girl’s bare feet that gripped the bare back of her proud and ridiculous mount. The enchantment grew not out of anything that happened or was performed but out of something that seemed to go round and around and around with the girl, attending her, a steady gleam in the shape of a circle—a ring of ambition, of happiness, of youth. (And the positive pleasures of equilibrium under difficulties.) In a week or two all would be changed, all (or almost all) lost: the girl would wear makeup, the horse would wear gold, the ring would be painted, the bark would be clean for the feet of the horse, the girl’s feet would be clean for the slippers she’d wear. All, all would be lost.

As I watched with the others, our jaws adroop, our eyes alight, I became painfully conscious of the element of time. Everything in the hideous old building seemed to take the shape of a circle, conforming to the course of the horse. The rider’s gaze, as she peered straight ahead, seemed to be circular, as though bent by force of circumstance; then time itself began running in circles, so the beginning was where the end was, and the two were the same, and one thing ran into the next and time went round and round and got nowhere. The girl wasn’t so young that she did not know the delicious satisfaction of having a perfectly behaved body and the fun of using it to do a trick most people can’t do, but she was too young to know that time does not really move in a circle at all. I thought: “She will never be as beautiful as this again”—a thought that made me acutely unhappy—and a flash in my mind (which is too much of a busybody to suit me) had projected her twenty-five years ahead, and she was now in the center of the ring, on foot, wearing a conical hat and hi-heeled shoes, the image of the older woman, holding the long rein, caught in the treadmill of an afternoon long in the future. “She is at that enviable moment in life [I thought] when she believes she can go once around the ring, make one complete circuit, and at the end be exactly the same age as at the start. Everything in her movements, her expression, told you that for her the ring of time was perfectly formed, changeless, predictable, without beginning or end, like the ring in which she was traveling at this moment with the horse that wallowed under her. And then I slipped back into my trance and time was circular again—time, passing quietly with the rest of us, so as not to disturb the balance of a performer.

Her ride ended as casually as it had begun. The older woman stopped the horse, and the girl slid to the ground. As she walked toward us to leave, there was a quick, small burst of applause. She smiled broadly, in surprise and pleasure; then her face suddenly regained its gravity and she disappeared through the door.

It has been ambitious and plucky of me to attempt to describe what is indescribable, and I have failed, as I knew I would. But I have discharged my duty to my society; and besides, a writer, like an acrobat, must occasionally try a stunt that is too much for him. At any rate, it is worth reporting that long before the circus comes to town, its most notable performances have already been given. Under the bright lights of the finished show, a performer need only reflect the electric candle power that is directed upon him; but in the dark and dirty old training rings and in the makeshift cages, whatever light is generated, whatever excitement, whatever beauty, must come from original sources—from internal fires of professional hunger and delight, from the exuberance and gravity of youth. It is the difference between planetary light and the combustion of stars.

The Death of the Moth (1942)

VIRGINIA WOOLF

Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) exposed the difficulties of being a woman writer in her essay “A Room of One’s Own.” Her novels experimented with time and narrative, and she is considered a master of the stream-of-consciousness technique. Woolf bat- tled mental illnesses throughout her life, and eventually committed suicide by drowning herself in 1941, a year before this essay was published. As you read, exam- ine the ways she presents images of life and death.

Moths that fly by day are not properly to be called moths; they do not excite that pleasant sense of dark autumn nights and ivy-blossom which the commonest yellow-underwing asleep in the shadow of the curtain never fails to rouse in us. They are hybrid creatures, neither gay like butterflies nor somber like their own species. Nevertheless the present specimen, with his narrow hay-colored wings, fringed with a tassel of the same color, seemed to be content with life. It was a pleasant morning, mid-September, mild, benignant, yet with a keener breath than that of the summer months. The plough was already scoring the field opposite the window, and where the share had been, the earth was pressed flat and gleamed with moisture. Such vigor came rolling in from the fields and the down beyond that it was difficult to keep the eyes strictly turned upon the book. The rooks too were keeping one of their annual festivities; soaring round the tree tops until it looked as if a vast net with thousands of black knots in it had been cast up into the air; which, after a few moments sank slowly down upon the trees until every twig seemed to have a knot at the end of it. Then, suddenly, the net would be thrown into the air again in a wider circle this time, with the utmost clamor and vociferation, as though to be thrown into the air and settle slowly down upon the tree tops were a tremendously exciting experience.

The same energy which inspired the rooks, the ploughmen, the horses, and even, it seemed, the lean bare-backed downs, sent the moth fluttering from side to side of his square of the windowpane. One could not help watching him. One, was, indeed, conscious of a queer feeling of pity for him. The possibilities of plea- sure seemed that morning so enormous and so various that to have only a moth’s part in life, and a day moth’s at that, appeared a hard fate, and his zest in enjoy- ing his meager opportunities to the full, pathetic. He flew vigorously to one cor- ner of his compartment, and, after waiting there a second, flew across to the other. What remained for him but to fly to a third corner and then to a fourth? That was all he could do, in spite of the size of the downs, the width of the sky, the far-off smoke of houses, and the romantic voice, now and then, of a steamer out at sea. What he could do he did. Watching him, it seemed as if a fiber, very thin but pure, of the enormous energy of the world had been thrust into his frail and diminutive body. As often as he crossed the pane, I could fancy that a thread of vital light became visible. He was little or nothing but life.

Yet, because he was so small, and so simple a form of the energy that was rolling in at the open window and driving its way through so many narrow and intricate corridors in my own brain and in those of other human beings, there was something marvelous as well as pathetic about him. It was as if someone had taken a tiny bead of pure life and decking it as lightly as possible with down and feathers, had set it dancing and zigzagging to show us the true nature of life. Thus displayed one could not get over the strangeness of it. One is apt to forget all about life, seeing it humped and bossed and garnished and cumbered so that it has to move with the greatest circumspection and dignity. Again, the thought of all that life might have been had he been born in any other shape caused one to view his simple activities with a kind of pity.

After a time, tired by his dancing apparently, he settled on the window ledge in the sun, and, the queer spectacle being at an end, I forgot about him. Then, looking up, my eye was caught by him. He was trying to resume his dancing, but seemed either so stiff or so awkward that he could only flutter to the bottom of the windowpane; and when he tried to fly across it he failed. Being intent on other matters I watched these futile attempts for a time without thinking, unconsciously waiting for him to resume his flight, as one waits for a machine, that has stopped momentarily, to start again without considering the reason of its failure. After perhaps a seventh attempt he slipped from the wooden ledge and fell,

fluttering his wings, on to his back on the windowsill. The helplessness of his attitude roused me. It flashed upon me that he was in difficulties; he could no longer raise himself; his legs struggled vainly. But, as I stretched out a pencil, meaning to help him to right himself, it came over me that the failure and awkwardness were the approach of death. I laid the pencil down again.

The legs agitated themselves once more. I looked as if for the enemy against which he struggled. I looked out of doors. What had happened there? Presum- ably it was midday, and work in the fields had stopped. Stillness and quiet had re- placed the previous animation. The birds had taken themselves off to feed in the brooks. The horses stood still. Yet the power was there all the same, massed out- side, indifferent, impersonal, not attending to anything in particular. Somehow it was opposed to the little hay-colored moth. It was useless to try to do anything. One could only watch the extraordinary efforts made by those tiny legs against an oncoming doom which could, had it chosen, have submerged an entire city, not merely a city, but masses of human beings; nothing, I knew had any chance against death. Nevertheless after a pause of exhaustion the legs fluttered again. It was superb this last protest, and so frantic that he succeeded at last in righting himself. One’s sympathies, of course, were all on the side of life. Also, when there was nobody to care or to know, this gigantic effort on the part of an insignificant little moth, against a power of such magnitude, to retain what no one else valued or desired to keep, moved one strangely.

Again, somehow, one saw life, a pure bead. I lifted the pencil again, useless though I knew it to be. But even as I did so, the unmistakable tokens of death showed themselves. The body relaxed, and instantly grew stiff. The struggle was over. The insignificant little creature now knew death. As I looked at the dead moth, this minute wayside triumph of so great a force over so mean an antagonist filled me with wonder. Just as life had been strange a few minutes before, so death was now as strange. The moth having righted himself now lay most decently and uncomplainingly composed. O yes, he seemed to say, death is stronger than I am.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION AND WRITING

1. Conduct a Toulmin analysis of Woolf’s essay. What is her claim? What are her reasons to support that claim? What are the warrants that underlie the claim?

2. What is Woolf’s purpose in writing this essay? To explore? inform? convince? meditate or pray?

3. Why has this essay endured for sixty years? What makes it memorable, lasting?

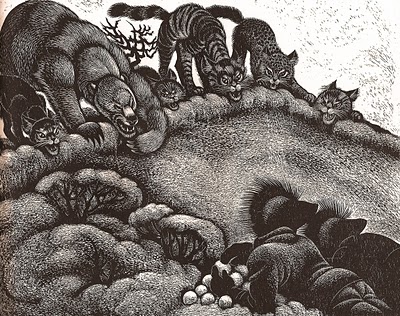

The Scotty Who Knew Too Much

by James Thurber

Several summers ago there was a Scottie who went to the country for a visit. He decided that all the farm dogs were cowards because they were afraid of a certain animal that had a white stripe down its back.

“You are a pussycat and I can lick you,” the Scottie said to the farm dog who lived in the house where the Scottie was visiting. “I can lick the animal with the white stripe too. Show him to me.”

“Don’t you want to ask any questions about him?” said the farm dog.

“Nah,” said the Scottie. “You ask the questions.”

So the farm dog took the Scottie into the woods and showed him the white-striped animal, and the Scottie closed in on him, growling and slashing. It was all over in a moment, and the Scottie lay on his back.

When he came to, the farm dog said, “What happened?”

“He threw vitriol,” said the Scottie, “but he never laid a glove on me.”

A few days later the farm dog told the Scottie there was another animal all the farm dogs were afraid of.

“Lead me to him,” said the Scottie. “I can lick anything that doesn’t wear horseshoes.”

“Don’t you want to ask any questions about him?” said the farm dog.

“Nah,” said the Scottie. “Just show me where he hangs out.” So the farm dog led him to a place in the woods and pointed out the little animal when he came along.

“The clown,” said the Scottie. “A pushover.” And he closed in, leading with his left and exhibiting some mighty fancy footwork. In less than a second, the Scottie was flat on his back, and when he woke up the farm dog was pulling quills out of him.

“What happened?” said the farm dog.

“He pulled a knife on me,” said the Scottie. “But at least I’ve learned how you fight up here in the country, and now I’m going to beat you up.”

So he closed in on the farm dog, holding his nose with one front paw to ward off the vitriol and covering his eyes with the other front paw to keep out the knives. The Scottie couldn’t see his opponent, and he couldn’t smell his opponent, and he was so badly beaten that he had to be taken back to the city and put in a nursing home.

Moral? It is better to ask some of the questions than to know all the answers.

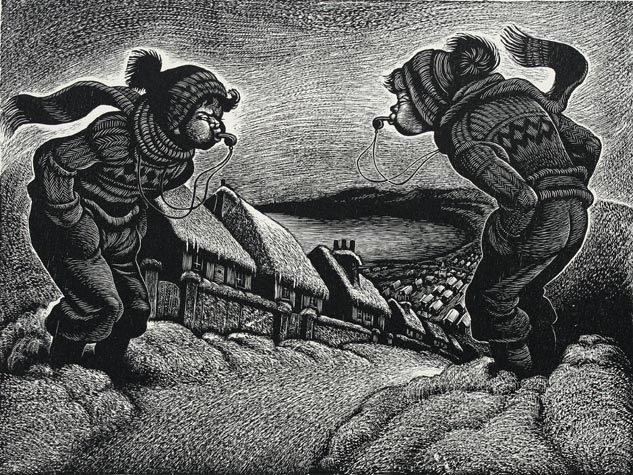

A Child’s Christmas in Wales

by Dylan Thomas

One Christmas was so much like another, in those years around the sea-town corner now and out of all sound except the distant speaking of the voices I sometimes hear a moment before sleep, that I can never remember whether it snowed for six days and six nights when I was twelve or whether it snowed for twelve days and twelve nights when I was six.

All the Christmases roll down toward the two-tongued sea, like a cold and headlong moon bundling down the sky that was our street; and they stop at the rim of the ice-edged fish-freezing waves, and I plunge my hands in the snow and bring out whatever I can find. In goes my hand into that wool-white bell-tongued ball of holidays resting at the rim of the carol-singing sea, and out come Mrs. Prothero and the firemen.

It was on the afternoon of the Christmas Eve, and I was in Mrs. Prothero’s garden, waiting for cats, with her son Jim. It was snowing. It was always snowing at Christmas. December, in my memory, is white as Lapland, though there were no reindeers. But there were cats. Patient, cold and callous, our hands wrapped in socks, we waited to snowball the cats. Sleek and long as jaguars and horrible-whiskered, spitting and snarling, they would slink and sidle over the white back-garden walls, and the lynx-eyed hunters, Jim and I, fur-capped and moccasined trappers from Hudson Bay, off Mumbles Road, would hurl our deadly snowballs at the green of their eyes. The wise cats never appeared.

We were so still, Eskimo-footed arctic marksmen in the muffling silence of the eternal snows – eternal, ever since Wednesday – that we never heard Mrs. Prothero’s first cry from her igloo at the bottom of the garden. Or, if we heard it at all, it was, to us, like the far-off challenge of our enemy and prey, the neighbor’s polar cat. But soon the voice grew louder.

“Fire!” cried Mrs. Prothero, and she beat the dinner-gong.

And we ran down the garden, with the snowballs in our arms, toward the house; and smoke, indeed, was pouring out of the dining-room, and the gong was bombilating, and Mrs. Prothero was announcing ruin like a town crier in Pompeii. This was better than all the cats in Wales standing on the wall in a row. We bounded into the house, laden with snowballs, and stopped at the open door of the smoke-filled room.

Something was burning all right; perhaps it was Mr. Prothero, who always slept there after midday dinner with a newspaper over his face. But he was standing in the middle of the room, saying, “A fine Christmas!” and smacking at the smoke with a slipper.

“Call the fire brigade,” cried Mrs. Prothero as she beat the gong.

“There won’t be there,” said Mr. Prothero, “it’s Christmas.”

There was no fire to be seen, only clouds of smoke and Mr. Prothero standing in the middle of them, waving his slipper as though he were conducting.

“Do something,” he said. And we threw all our snowballs into the smoke – I think we missed Mr. Prothero – and ran out of the house to the telephone box.

“Let’s call the police as well,” Jim said. “And the ambulance.” “And Ernie Jenkins, he likes fires.”

But we only called the fire brigade, and soon the fire engine came and three tall men in helmets brought a hose into the house and Mr. Prothero got out just in time before they turned it on. Nobody could have had a noisier Christmas Eve. And when the firemen turned off the hose and were standing in the wet, smoky room, Jim’s Aunt, Miss. Prothero, came downstairs and peered in at them. Jim and I waited, very quietly, to hear what she would say to them. She said the right thing, always. She looked at the three tall firemen in their shining helmets, standing among the smoke and cinders and dissolving snowballs, and she said, “Would you like anything to read?”

Years and years ago, when I was a boy, when there were wolves in Wales, and birds the color of red-flannel petticoats whisked past the harp-shaped hills, when we sang and wallowed all night and day in caves that smelt like Sunday afternoons in damp front farmhouse parlors, and we chased, with the jawbones of deacons, the English and the bears, before the motor car, before the wheel, before the duchess-faced horse, when we rode the daft and happy hills bareback, it snowed and it snowed. But here a small boy says: “It snowed last year, too. I made a snowman and my brother knocked it down and I knocked my brother down and then we had tea.”

“But that was not the same snow,” I say. “Our snow was not only shaken from white wash buckets down the sky, it came shawling out of the ground and swam and drifted out of the arms and hands and bodies of the trees; snow grew overnight on the roofs of the houses like a pure and grandfather moss, minutely -ivied the walls and settled on the postman, opening the gate, like a dumb, numb thunder-storm of white, torn Christmas cards.”

“Were there postmen then, too?”

“With sprinkling eyes and wind-cherried noses, on spread, frozen feet they crunched up to the doors and mittened on them manfully. But all that the children could hear was a ringing of bells.”

“You mean that the postman went rat-a-tat-tat and the doors rang?”

“I mean that the bells the children could hear were inside them.”

“I only hear thunder sometimes, never bells.”

“There were church bells, too.”

“Inside them?”

“No, no, no, in the bat-black, snow-white belfries, tugged by bishops and storks. And they rang their tidings over the bandaged town, over the frozen foam of the powder and ice-cream hills, over the crackling sea. It seemed that all the churches boomed for joy under my window; and the weathercocks crew for Christmas, on our fence.”

“Get back to the postmen”

“They were just ordinary postmen, fond of walking and dogs and Christmas and the snow. They knocked on the doors with blue knuckles ….”

“Ours has got a black knocker….”

“And then they stood on the white Welcome mat in the little, drifted porches and huffed and puffed, making ghosts with their breath, and jogged from foot to foot like small boys wanting to go out.”

“And then the presents?”

“And then the Presents, after the Christmas box. And the cold postman, with a rose on his button-nose, tingled down the tea-tray-slithered run of the chilly glinting hill. He went in his ice-bound boots like a man on fishmonger’s slabs.

“He wagged his bag like a frozen camel’s hump, dizzily turned the corner on one foot, and, by God, he was gone.”

“Get back to the Presents.”

“There were the Useful Presents: engulfing mufflers of the old coach days, and mittens made for giant sloths; zebra scarfs of a substance like silky gum that could be tug-o’-warred down to the galoshes; blinding tam-o’-shanters like patchwork tea cozies and bunny-suited busbies and balaclavas for victims of head-shrinking tribes; from aunts who always wore wool next to the skin there were mustached and rasping vests that made you wonder why the aunts had any skin left at all; and once I had a little crocheted nose bag from an aunt now, alas, no longer whinnying with us. And pictureless books in which small boys, though warned with quotations not to, would skate on Farmer Giles’ pond and did and drowned; and books that told me everything about the wasp, except why.”

“Go on the Useless Presents.”

“Bags of moist and many-colored jelly babies and a folded flag and a false nose and a tram-conductor’s cap and a machine that punched tickets and rang a bell; never a catapult; once, by mistake that no one could explain, a little hatchet; and a celluloid duck that made, when you pressed it, a most unducklike sound, a mewing moo that an ambitious cat might make who wished to be a cow; and a painting book in which I could make the grass, the trees, the sea and the animals any colour I pleased, and still the dazzling sky-blue sheep are grazing in the red field under the rainbow-billed and pea-green birds. Hardboileds, toffee, fudge and allsorts, crunches, cracknels, humbugs, glaciers, marzipan, and butterwelsh for the Welsh. And troops of bright tin soldiers who, if they could not fight, could always run. And Snakes-and-Families and Happy Ladders. And Easy Hobbi-Games for Little Engineers, complete with instructions. Oh, easy for Leonardo! And a whistle to make the dogs bark to wake up the old man next door to make him beat on the wall with his stick to shake our picture off the wall. And a packet of cigarettes: you put one in your mouth and you stood at the corner of the street and you waited for hours, in vain, for an old lady to scold you for smoking a cigarette, and then with a smirk you ate it. And then it was breakfast under the balloons.”

“Were there Uncles like in our house?”

“There are always Uncles at Christmas. The same Uncles. And on Christmas morning, with dog-disturbing whistle and sugar fags, I would scour the swatched town for the news of the little world, and find always a dead bird by the Post Office or by the white deserted swings; perhaps a robin, all but one of his fires out. Men and women wading or scooping back from chapel, with taproom noses and wind-bussed cheeks, all albinos, huddles their stiff black jarring feathers against the irreligious snow. Mistletoe hung from the gas brackets in all the front parlors; there was sherry and walnuts and bottled beer and crackers by the dessertspoons; and cats in their fur-abouts watched the fires; and the high-heaped fire spat, all ready for the chestnuts and the mulling pokers. Some few large men sat in the front parlors, without their collars, Uncles almost certainly, trying their new cigars, holding them out judiciously at arms’ length, returning them to their mouths, coughing, then holding them out again as though waiting for the explosion; and some few small aunts, not wanted in the kitchen, nor anywhere else for that matter, sat on the very edge of their chairs, poised and brittle, afraid to break, like faded cups and saucers.”

Not many those mornings trod the piling streets: an old man always, fawn-bowlered, yellow-gloved and, at this time of year, with spats of snow, would take his constitutional to the white bowling green and back, as he would take it wet or fire on Christmas Day or Doomsday; sometimes two hale young men, with big pipes blazing, no overcoats and wind blown scarfs, would trudge, unspeaking, down to the forlorn sea, to work up an appetite, to blow away the fumes, who knows, to walk into the waves until nothing of them was left but the two furling smoke clouds of their inextinguishable briars. Then I would be slap-dashing home, the gravy smell of the dinners of others, the bird smell, the brandy, the pudding and mince, coiling up to my nostrils, when out of a snow-clogged side lane would come a boy the spit of myself, with a pink-tipped cigarette and the violet past of a black eye, cocky as a bullfinch, leering all to himself.

I hated him on sight and sound, and would be about to put my dog whistle to my lips and blow him off the face of Christmas when suddenly he, with a violet wink, put his whistle to his lips and blew so stridently, so high, so exquisitely loud, that gobbling faces, their cheeks bulged with goose, would press against their tinsled windows, the whole length of the white echoing street. For dinner we had turkey and blazing pudding, and after dinner the Uncles sat in front of the fire, loosened all buttons, put their large moist hands over their watch chains, groaned a little and slept. Mothers, aunts and sisters scuttled to and fro, bearing tureens. Auntie Bessie, who had already been frightened, twice, by a clock-work mouse, whimpered at the sideboard and had some elderberry wine. The dog was sick. Auntie Dosie had to have three aspirins, but Auntie Hannah, who liked port, stood in the middle of the snowbound back yard, singing like a big-bosomed thrush. I would blow up balloons to see how big they would blow up to; and, when they burst, which they all did, the Uncles jumped and rumbled. In the rich and heavy afternoon, the Uncles breathing like dolphins and the snow descending, I would sit among festoons and Chinese lanterns and nibble dates and try to make a model man-o’-war, following the Instructions for Little Engineers, and produce what might be mistaken for a sea-going tramcar.

Or I would go out, my bright new boots squeaking, into the white world, on to the seaward hill, to call on Jim and Dan and Jack and to pad through the still streets, leaving huge footprints on the hidden pavements.

“I bet people will think there’s been hippos.”

“What would you do if you saw a hippo coming down our street?”

“I’d go like this, bang! I’d throw him over the railings and roll him down the hill and then I’d tickle him under the ear and he’d wag his tail.”

“What would you do if you saw two hippos?”

Iron-flanked and bellowing he-hippos clanked and battered through the scudding snow toward us as we passed Mr. Daniel’s house.

“Let’s post Mr. Daniel a snow-ball through his letter box.”

“Let’s write things in the snow.”

“Let’s write, ‘Mr. Daniel looks like a spaniel’ all over his lawn.”

Or we walked on the white shore. “Can the fishes see it’s snowing?”

The silent one-clouded heavens drifted on to the sea. Now we were snow-blind travelers lost on the north hills, and vast dewlapped dogs, with flasks round their necks, ambled and shambled up to us, baying “Excelsior.” We returned home through the poor streets where only a few children fumbled with bare red fingers in the wheel-rutted snow and cat-called after us, their voices fading away, as we trudged uphill, into the cries of the dock birds and the hooting of ships out in the whirling bay. And then, at tea the recovered Uncles would be jolly; and the ice cake loomed in the center of the table like a marble grave. Auntie Hannah laced her tea with rum, because it was only once a year.

Bring out the tall tales now that we told by the fire as the gaslight bubbled like a diver. Ghosts whooed like owls in the long nights when I dared not look over my shoulder; animals lurked in the cubbyhole under the stairs and the gas meter ticked. And I remember that we went singing carols once, when there wasn’t the shaving of a moon to light the flying streets. At the end of a long road was a drive that led to a large house, and we stumbled up the darkness of the drive that night, each one of us afraid, each one holding a stone in his hand in case, and all of us too brave to say a word. The wind through the trees made noises as of old and unpleasant and maybe webfooted men wheezing in caves. We reached the black bulk of the house. “What shall we give them? Hark the Herald?”

“No,” Jack said, “Good King Wencelas. I’ll count three.” One, two three, and we began to sing, our voices high and seemingly distant in the snow-felted darkness round the house that was occupied by nobody we knew. We stood close together, near the dark door. Good King Wencelas looked out On the Feast of Stephen … And then a small, dry voice, like the voice of someone who has not spoken for a long time, joined our singing: a small, dry, eggshell voice from the other side of the door: a small dry voice through the keyhole. And when we stopped running we were outside our house; the front room was lovely; balloons floated under the hot-water-bottle-gulping gas; everything was good again and shone over the town.

“Perhaps it was a ghost,” Jim said. ”

Perhaps it was trolls,” Dan said, who was always reading.

“Let’s go in and see if there’s any jelly left,” Jack said. And we did that.

Always on Christmas night there was music. An uncle played the fiddle, a cousin sang “Cherry Ripe,” and another uncle sang “Drake’s Drum.” It was very warm in the little house. Auntie Hannah, who had got on to the parsnip wine, sang a song about Bleeding Hearts and Death, and then another in which she said her heart was like a Bird’s Nest; and then everybody laughed again; and then I went to bed. Looking through my bedroom window, out into the moonlight and the unending smoke-colored snow, I could see the lights in the windows of all the other houses on our hill and hear the music rising from them up the long, steady falling night. I turned the gas down, I got into bed. I said some words to the close and holy darkness, and then I slept.

Advice to Youth

by Mark Twain (1835-1910)