Micah Pietraho

Especially before the 20th century’s great increase in alternate means, mainly television and radio, books dominated the communication of narrative, the primary provider of entertainment and intellectual discussion. Writers commanded great celebrity; publishers much wealth. Despite their influence, some of the most popular authors of their respective times and audiences are effectively forgotten in modern culture. This is due to a changed understanding of their work; the audience is not that which was intended. The lack of common context has divided the writer and the reader. This schism could have been created through any subset of a great number of factors, including cultural references and implicit biases. Similarly, the employment of allegory, despite its obvious contribution to a reader’s understanding of an abstract argument and ability to serve as a means of conveying subtlety, is highly dependent on cultural context and can quickly become ambiguous.

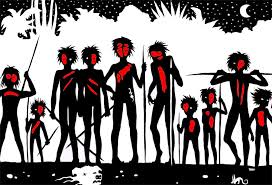

Allegory, including the religious symbolism in “Lord of the Flies,” is highly dependent on social knowledge only able to be delivered through the particular cultural context of the work. Simon is recognized from an early point in “Lord of the Flies” as a central character, his introduction being dramatic as he, with no warning, “flopped on his face in the sand” (12). For much of the, however, his importance is unclear, Simon only contributing passive companionship and a few mumbling remarks at the assembly. Already on high alert, after noticing that the title of the book, “Lord of the Flies,” is a name for the devil, the reader may pick up on the reference in Simon’s name to either the Old Testament’s Simeon, son of Jacob, or the New Testament’s Simon, later renamed Peter, the head apostle. Although both of these religious figures share enlightening traits with Simon, their primary role is to accentuate Simon’s nature as a Jesus-like figure: he alone, besides unrespected Piggy, understands the true nature of the beast; he is then “sacrificed” in a tribal ritual. The specific knowledge that detecting these meanings is broad. A general outline of the New Testament must be understood in order recognize Simon as a Jesus-like character. Only noticing this, however, grossly simplifies the religious nature of the book and the implications of the references. Names, such as “the Lord of the Flies” and “Simon,” are obscure to even many pious individuals. These few religious elements are still probably only a fraction of all those included by Golding; they are only hose picked up on by the author, a young, reform Jew, one hardly familiar with the intricacies of the New Testament. “Lord of the Flies” was written, if only 65 years ago, in a region and a context where religion was emphasized much more strongly. The absence of this context hinders the modern reader’s understanding of his allegory.

While enough social context remains to understand some of Golding’s religious symbolism, other aspects of his allegory, primarily the political, have become ambiguous. Although patterns can be detected, specific references are no longer able to determine the political message. Clearly, two groups exist: one including Ralph, Piggy, and Samneric, the other Jack and the choir boys. Simon belongs to both yet neither of these two groups. In addition to the division of the population into sections with different leanings and philosophies, a clear evolution of the political structure emerge, from democracy to anarchy to dictatorship, with the transitions from the original “conch and . . . assembly” (24) to Jack’s tribe. Such clear models of political structures and representations of social groups are indicative of political allegories, including “Animal Farm” and “The Wizard of Oz.” It is unclear, however, what political conflict Golding intended to depict. Writing after World War II, he could have intended to portray Germany’s struggle with Europe. With bleak economic futures, German citizens supported leaders who assigned the blame arbitrarily and took action as to punish the Jews for causing the experienced depression. With a low prospect of rescue, the shipwrecked, British boys supported Jack, founder of the tribe, who, in his tribal dance, called out that Simon, who had just came “crawling out of the forest . . . uncertainly,” (115) was the beast, causing the tribe to kill Simon. Similarly, the narrative could represent the Cold War, which was also under way in 1954. The prosperity under the democracy immediately formed by Ralph and Piggy is emphasized. Golding ensures that all the qualities of the United States and the free world are included in this period: democracy is dominant; much freedom existed in schedule and actions; all individuals were essentially equal. Later, as Jack’s tribe gained dominance, Soviet elements were displayed: Jack served as the highly centralized government; resources were divided only after passing through this centralized locus; certain individuals were granted special privileges, most notably Roger. Both of these outlines of allegory seem plausible and even likely. Golding must have had one in mind, which was probably equally as clear to his contemporary audience. Today, however, the details of the allegory have been obscured, smudged into the narrative, simplifying the book. Some ambiguity arises as time passes and social context is lost.

In contrast to his others, Golding’s social allegory seems clear and eternal, documenting the interactions between different cultural factors in the decline of civilization and humanity. Even in this case, however, the medium of allegory limits the complexity of his message, grossly oversimplifying a highly complex issue. Despite its obvious application and merits, allegory relies heavily on social context. Even when the themes are general enough to transcend boundaries, it lacks the complexity to not oversimplify the argument. Both people and inanimate objects are used as symbols. For example, Piggy, quite obviously, stands in for reason throughout the narrative. Similarly, Ralph and his influence represent the hope maintained by the group. He constantly reminds the group that “‘we must make a fire,’” (26) the only means by which they can be rescued; the group loses hope as Ralph loses influence. Other characters, such as Jack, Roger, and Simon, symbolize concepts, such as ambition, cruelty, and compassion; objects, such as Piggy’s glasses and the conch, the application of reason and civilization. If I, as an individual, have failed to identify major symbols, it is a testament to changing social themes. If all are described, however, the allegory is ineffective, oversimplifying Golding’s complex point. For example, characters must act fore mostly as drivers of the plot, only secondly as symbols, diluting their effect. While he is present, representing cruelty, throughout, Roger suggests that he group should “‘have a vote’” (14) to elect the chief, a role Ralph will clearly fill. Cruelty has no business legitimizing hope other than to move along the plot. Furthermore, factors seemingly vital to society have been omitted, Golding being unable to fold all aspects of culture into “Lord of the Flies.” Why was compassion represented but not trust; why reason not justice; why fear not doubt? Golding was not sloppy but was forced to arbitrarily choose a finite number a social factor to emphasize. The nature of allegory to subject itself to plot, implying this restriction, prevents it from allowing an argument on a complex issue to be expressed.

William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” is rich with allegory. This allegory, however, is being eroded as cultural context is lost, rendering modern audiences unable to fully identify or understand the implications of the symbolism. Even when the allegory is current and understandable, the device lacks the robust nature required to fully encapsulate broad topics. Due to this constant degradation of the quality of allegory, historical authors can no longer be fully appreciated; their work cannot be fully understood. This is exactly the value of new literature, however. It allows the allegory and text as a whole to be appreciated fully, as the cultural context is shared between the narrative and the audience. Historical works, even as recent as “Lord of the Flies,” must still be appreciated, however, if not fully understood; if cultural biases are accounted for, all great literature is transcendent.