A MICKEY MANTLE KOAN The obstinate grip of an autographed baseball

BY: David James Duncan

On April 6, 1965, my brother, Nicholas John Duncan, died of what his surgeons called “complications” after three unsuccessful open-heart operations. He was seventeen at the time-four years my elder to the very day. He’d been the fastest sprinter in his high school class until the valve in his heart began to close, but he was so bonkers about baseball that he’d preferred playing a mediocre JV shortstop to starring at varsity track. As a ballplayer he was a competent fielder, had a strong and fairly accurate arm, and stole bases with ease-when he could reach them. But no matter how much he practiced or what stances, grips, or self-hypnotic tricks he tried, he lacked the hand/eye magic that consistently lays bat-fat against ball, and remained one of the weakest hitters on his team.

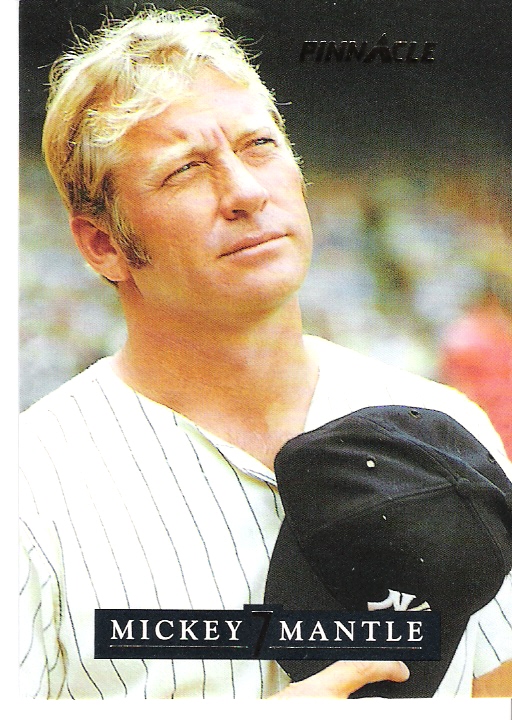

John lived his entire life on the out- skirts of Portland, Oregon-637 miles from the nearest major league team. In franchiseless cities in the Fifties and early Sixties there were two types of fans: those who thought the Yankees stood for everything right with America, and those who thought they stood for everything wrong with it. My brother was an extreme manifestation of the former type. He conducted a one-man campaign to notify the world that Roger Maris’s sixty-one homers in ’61 came in three fewer at bats than Babe Ruth’s sixty in ’27. He maintained-all statistical evidence to the contrary-that Clete Boyer was a better third baseman than his brother, Ken, simply because Clete was a Yankee. He may not have been the only kid on the block who considered Casey Stengel the greatest sage since Solomon, but I’m sure he was the only one who considered Yogi Berra the second greatest. And, of course, Mickey Mantle was his absolute hero, but his tragic hero. The Mick, my brother maintained, was the greatest raw talent of all time. He was one to whom great gifts were given, from whom great gifts had been ripped away; and the more scarred his knees became, the more frequently he fanned, the more flagrant his limp and apologetic his smile, the more John revered him. And toward this single Yankee I, too, was able to feel a touch of reverence, if only because on the subject of scars I considered my brother an unimpeachable authority: he’d worn one from the time he was eight,

compliments of the Mayo Clinic, that wrapped clear around his chest in a wavy line, like stitching round a clean white baseball. Yankees aside, John and I had more in common than a birthday. We bickered regularly with our middle brother and little sister, but almost never with each other. We were both bored, occasionally to insurrection, by schoolgoing, churchgoing, and any game or sport that didn’t involve a ball. We both preferred, as a mere matter of style, Indians to cowboys, hoboes to businessmen, Buster Keaton to Charlie Chaplin, Gary Cooper to John Wayne, deadbeats to brownnosers, and even brownnosersto ElvisPresley. We shared a single cake on our joint birthday, in- variably annihilating the candle flames with a tandem blowing effort, only to realize that we’d once again forgotten to make a wish. And when the parties were over or the house was stuffy, the parents cranky or the TV shows insufferably dumb, whenever we were rest- less, punchy, or just feeling as if there was nothing to do, catch-with a hard ball-is what John and I did.

We were not exclusive, at least not by intention: our father and middle brother and an occasional cousin or friend would join us now and then. But something in most everyone else’s brain or bloodstream sent them bustling off to less contemplative en- deavors before the real rhythm of the thing ever took hold. Genuine catch- playing occurs in a double limbo be- tween busyness and idleness, and between what is imaginary and what is real. Also, as with any contemplative pursuit, it takes time, and the ability to forget time, to slip into this dual limbo and to discover (i.e., lose) oneself in the music of the game.

It helps to have a special place to play. Ours was a shaded, ninety-foot corridor between one neighbor’s apple orchard and the other’s stand of old- growth Douglas firs, on a stretch of lawn so lush and mossy it sucked the heat out of even the hottest grounders. I always stood in the north, John in the south. We might call balls and strikes for an imaginary inning or two, or maybe count the number of errorless catches and throws we could make (300s were common, and our record was high in the 800s). But the deep shade, the 200-foot firs, the mossy footing and fragrance of apples all made it a setting more conducive to mental vacationing than to any kind of disciplined effort. During spring-training months our catch occasionally started as a drill-a grounder, then a peg; an- other grounder, a peg. But as our movements became fluid and the throws brisk and accurate, the pretense of practice would inevitably fade, and we’d just aim for the chest and fire, hisssss POP! hisssss POP! until a meal, a duty, or total darkness forced us to recall that this was the real world in which even timeless pursuits come to an end.

Our talk must have seemed strange to eavesdroppers. We lived in our bod- ies during catch, and our minds and mouths, though still operative, were just along for the ride. Most of the noise I made was with the four or five pieces of Bazooka I was invariably working over, though when the gum turned bland, I’d sometimes narrate our efforts in a stream-of-doggerelplay- by-play. My brother’s speech was less voluminous and a bit more coherent, but of no greater didactic intent: he just poured out idle litanies of Yankee worship or even idler braggadocio ala DizzyDean, all of it artfully spiced

with spat sunflower-seed B husks.

But one day when we were-six- teen and twelve, respectively, my big brother surprised me out there in our corridor. Snagging a low’ throw, he closed his mitt round the ball, stuck it under his arm, stared off into the trees, and got serious with me for a minute. All his life, he said, he’d struggled to be a shortstop and a hitter, but he was older now, and had a clearer notion of what he could and couldn’t do. It was time to get practical, he said. Time to start developing obvious strengths and evading flagrant weaknesses. “So I’ve decided,” he concluded, “to become a junk pitcher.”

I didn’t believe a word of it. My brother had been a “slugger worshiper” from birth. He went on embellishing his idea, though, and .even made it sound rather poetic: to foil some muscle-bound fence-buster with an off- speed piece of crap that blupped off his bat like cow custard-this, he maintained, was the pluperfect pith of an attribute he called Solid Cool.

I didn’t recognize until months lat- er just how carefully considered this new junk-pitching jag had been. That John’s throwing arm was better than his batting eye had always been obvious, and it made sense to exploit that. But there were other factors he didn’t mention: like the sharp pains in his chest every time he took a full swing, or the new ache that half-blinded and sickened him whenever he ran full speed. Finding the high arts of slug- ging and base stealing physically im- possible, he’d simply lowered his sights enough to keep his baseball dreams alive. No longer able to emulate his heroes, he set out to bamboozle those who thought they could. To that end he’d learned a feeble knuckler, a round- house curve, a submarine fastball formidable solely for its lack of accuracy, and was trashing his arm and my patience with his attempts at a screw- ball, when his doctors informed our family that a valve in his heart was rapidly closing. He might live as long as five years if we let it go, they said, but immediate surgery was best, since his recuperative powers were greatest now.

John said nothing about any of this. He just waited until the day he was due at the hospital, snuck down to the stable where he kept his horse, saddled her up, and galloped away. He rode about twenty miles, to the farm of a friend, and stayed there in hiding for nearly two weeks. But when he snuck home one morning for clean clothes and money, my father and a neighbor caught him, and first tried to force him but finally convinced him to have the operation and be done with it.

Once in the hospital he was cooperative, cheerful, and unrelentingly courageous. He survived second, third, and fourth operations, several stop- pings of the heart, and a nineteen-day coma. He recovered enough at one point, even after the coma, to come home for a week or so. But the over- riding “complication” to which his principal surgeon kept making oblique references turned out to be a heart so ravaged by scalpel wounds that an artificial valve had nothing but shreds to be sutured to. Bleeding internally, pissing blood, John was moved into an oxygen tent in an isolated room, where he remained fully conscious, and fully determined to heal, for two months after his surgeons had abandoned him. And, against all odds, his condition stabilized, then began to improve. The doctors reappeared and began to discuss, with obvious despair, the feasibility of a fifth operation.

Then came the second “complication”: staph. Overnight, we were reduced from genuine hope to awkward pleas for divine intervention. We invoked no miracles. Two weeks after A contracting the infection, my brother died.

At his funeral, a preacher who didn’t know John from Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis eulogized him so lavishly and inaccurately that I was moved to a state of tearlessness that lasted for four years. It’s an unenviable task to try to make public sense of a private catastrophe you know little about. But had I been in that preacher’s shoes, I would have mentioned one or two of my brother’s actual attributes, if only to reassure late-arriving mourners that they hadn’t wandered into the wrong funeral. The person we were endeavoring to miss had, for instance, been a C student all his life, had smothered everything he ate with ketchup, had diligently avoided all forms of work that didn’t involve horses, and had frequently gone so far as to wear sunglasses in- doors in the relentless quest for Solid Cool. He’d had the disconcerting habit of sound-testing his pleasant baritone voice by bellowing “Beeeeeee- -ooooooo1″down any alley or hallסoס0 way that looked like it might contain an echo. He’d had an interesting, slangy obliviousness to proportion: any altercation, from a fistfight to a world war, was “a rack”; any authority, from our mother to the head of the U.N., was “the Brass”; any pest, from the kid next door to Khrushchev, was “a buttwipe”; and any kind of ball, from a BB to the sun, was “the orb.” He was brave: whenever anybody his age harassed me, John warned them once and beat them up the second time, or got beat up trying. He was also unabashedly, majestically vain. He referred to his person, with obvious pride, as “the Bod.” He was an immaculate dresser. And he loved to stare at himself publicly or privately-

in mirrors, windows, puddles, chrome car-fenders, upside-down in tea- spoons-and to solemnly comb his long auburn hair over and over again, like his hero, Edd {“Kookie”}Byrnes, on 77Sunset Strip.

His most astonishing attribute, to me at least, was his never-ending skein of girlfriends. He had a simple but apparently efficient rating system for all female acquaintances: he called it “percentage of Cool versus percent- age of Crud.” A steady girlfriend usually weighed in at around 95 percent Cool, 5 percent Crud, and if the Crud level reached 10 percent it was time to start quietly looking elsewhere. Only two girls ever made his “100 percent Cool List,” and I was struck by the fact that neither was a girlfriend and one wasn’t even pretty: whatever “100 percent Cool” was, it was not skin- deep. No girl ever came close to a “100 percent Crud” rating, by the way: my brother was chivalrous.

John was not religious. He believed in God, but passively, with nothing like the passion he had for the Yankees. He seemed a little more friendly with Jesus. “Christ is cool,” he’d say, if forced to show his hand. But I don’t recall him speaking of any sort of goings-on between them until he casually mentioned, a day or two before he died, a conversation they’d just had, there in the oxygen tent. And even then John was John: what impressed him even more than the fact of Christ’s presence or the consoling words He spoke was the A natty suit and tie He was wearing.

On the morning after his death, April 7, 1965, a small brown-paper package arrived at our house, special delivery from New York City,addressed to John. I brought it to my mother and leaned over her shoulder as she sat down to study it. Catching a whiff of antiseptic, I thought at first that it came from her hair: she’d spent the last four months of her life in a straight- back chair by my brother’s bed, and hospital odors had permeated her. But the smell grew stronger as she began to unwrap the brown paper, until I realized it came from the object inside.

It was a small, white, cylindrical, cardboard bandage box. “Johnson & Johnson,” it said in red letters. “12 inches x 10 yards,” it added in blue. Strange. Then I saw it had been split in half by a knife or a scalpel and bound back together with adhesive tape: so there was another layer,some- thing hiding inside.

My mother smiled as she began to rip the tape away. At the same time, tears were landing in her lap. Then the tape was gone, the little cylinder fell away, and inside, nested in tissue, was a baseball. Immaculate white leather. Perfect red stitching. On one cheek, in faint green ink, the signature of American League president Joseph Cronin and the trademark REACH. THE SIGN OF QUALITY. And on the opposite cheek, with bright blue ballpoint ink, a tidy but flowing hand had written, To John-My Best Wishes. Your Pal, Mickey Mantle. April 6, 1965.

The ball dwelt upon our fireplace mantel-an unintentional pun on my mother’s part. We used half the John- son & Johnson box as a pedestal, and for years I saved the other half, figuring that the bandage it once contained had held Mantle’s storied knee together for a game.

Even after my mother explained that the ball came not out of the blue but in response to a letter, I considered it a treasure. I told all my friends about it, and invited the closest to stop by and gawk. But gradually I began to see that the public reaction to the ball was disconcertingly predictable. The first response was usually, “Wow! Mickey Mantle!” But then they’d get the full story: “Mantle signed it the day he died? Your brother never even saw it?” And that made them un- comfortable. This was not at all the way an autographed baseball was sup- posed to behave. How could an im- mortal call himself your “Pal,” how could you be the recipient of The Mick’s “Best Wishes,” and still just lie back and die?

I began to share the discomfort. Over the last three of my thirteen years I’d devoured scores of baseball. books, all of which agreed that a bat, program, mitt, or ball signed by a big- league hero was a sacred relic, that we should expect such relics to have magical properties, and that they would prove pivotal in a young protagonist’s life.Yet here I was,the young protagonist. Here was my relic. And all the damned thing did, before long, was depress and confuse me.

I stopped showing the ball to people, tried ignoring it, found that this was impossible, tried instead to pre- tend that the blue ink was an illegible scribble and that the ball was just a ball. But the ink wasn’t illegible: it never stopped saying just what it said. So finally I picked the ball up and studied it, hoping to discover exactly why I found it so troublesome. Feigning the cool rationality I wished I’d felt, I told myself that a standard sports hero had received a letter from a standard distraught mother, had signed, packaged, and mailed off the standard ingratiatingly heroic response, had failed to think that the boy he in- scribed the ball to might be dead when it arrived, and so had mailed his survivors a blackly comic non sequitur. I then told myself, “That’s all there is to it”-which left me no option but to pretend that I hadn’t expected or wanted any more from the ball than I got, that I’d harbored no desire for any sort of sign, any imprimatur, any flicker of recognition from an Above or a Beyond. I then began falling to pieces for lack of that sign.

Eventually, I got honest about Mantle’s baseball: I picked the damned thing up, read it once more, peered as far as I could inside myself, and admitted for the first time that I was pissed. As is always the case with arriving baseballs, timing is the key- and this cheery little orb was inscribed on the day its recipient lay dying and arrived on the day he was being embalmed! This was not a harmless coincidence: it was the shabbiest, most embittering joke that Providence had ever played on me. My best friend and brother was dead, dead, dead, and Mantle’s damned ball and best wish- es made that loss even less tolerable, and that, I told myself, really was all there was to it.

I hardened my heart, quit the baseball team, went out for golf, practiced like a zealot, cheated like hell, kicked my innocuous, naive little opponents all over the course. I sold the beautiful outfielder’s mitt that I’d inherited from my brother for a pittance.

But, as is usual in baseball stories, that wasn’t all there was to it.

I’d never heard of Zen koans at the time, and Mickey Mantle is certainly no roshi. But baseball and Zen are two pastimes that Americans and Japanese have come to revere almost equally: roshis are men famous for hit- ting things hard with a big wooden stick; a koan is a perfectly nonsensical or nonsequacious statement given by an old pro (roshi) to a rookie (layman or monk); and the stress of living with and meditating upon a piece of mind- numbing nonsense is said to eventually prove illuminating. So I know of no better way to describe what the message on the ball became for me than to call it a koan.

In the first place, the damned thing’s batteries just wouldn’t run down. For weeks, months, years, every time 1 saw those nine blithely blue- inked words they knocked me off balance like a sudden shove from behind. They were an emblem of all the false assurances of surgeons, all the futile prayers of preachers, all the hollowness of Good-Guys-Can’t-Lose baseball stories I’d ever heard or read. They were a throw I’d never catch. And yet … REACH, the ball said. THE SIGN OF QUALITY.

So year after year I kept trying, kept hoping to somehow answer the koan.

I became an adolescent, enrolling my body in the obligatory school of pain-without-dignity called “puberty,” nearly flunking, then graduating almost without noticing. I discovered in the process that some girls were nothing like 95 percent Crud. I also discovered that there was life after baseball, that America was not the Good Guys, that God was not a Christian, that I preferred myth to theology, and that, when it came to heroes, the likes of Odysseus, Rama, and Finn MacCool meant incomparably more to me than the George Washingtons, Davy Crocketts, and Babe Ruths I’d been force-fed. I discovered (some- times prematurely or over abundantly, but never to my regret) metaphysics, wilderness, Europe, black tea, high lakes, rock, Bach, tobacco, poetry, trout streams, the Orient, the novel, my life’s work, and a hundred other grown-up tools and toys. But amid these maturations and transformations there was one unwanted constant: in the presence of that confounded ball, I remained thirteen years old. One peek at the “Your Pal” koan and what- ever maturity or wisdom or equanimity I possessed was repossessed, leaving

me as irked as any stumped monk or slumping slugger.

It took four years to solve the riddle on the ball. It was autumn when it happened-the same autumn during which I’d grown older than my brother would ever be. As often hap- pens with koan solutions, I wasn’t even thinking about the ball at the time. As is also the case with koans, I can’t possibly describe in words the impact of the response, the instantaneous healing that took place, or the ensuing sense of lightness and release. But I’ll say what I can.

The solution came during a fit of restlessness brought on by a warm Indian summer evening. I’d just finished watching the Miracle Mets blitz the Orioles in the World Series, and was standing alone in the living room, just staring out at the yard and the fading sunlight, feeling a little stale and fidgety, when I realized that this was just the sort of fidgets I’d never had to suffer when John was alive-because we’d always work our way through them with a long game of catch.With that thought, and at that moment, I simply saw my brother catch, then throw a baseball. It occurred neither in an indoors nor an outdoors. It lasted a couple of seconds, no more. But I saw him so clearly, and he then vanished so completely, that my eyes blurred, my throat and chest ached, and I didn’t need to see Mantle’s base- ball to realize exactly what I’d want- ed from it all along:

From the moment I’d first laid eyes on it, all I’d wanted was to take that immaculate ball out to our corridor on an evening just like this one, to take my place near the apples in the north, and to find my brother waiting beneath the immense firs to the south. All I’d wanted was to pluck that too- perfect ball off its pedestal and pro- ceed, without speaking, to play catch so long and hard that the grass stains and nicks and the sweat of our palms would finally obliterate every last trace of Mantle’s blue ink, until all he would have given us was a grass-green,earth- brown, beat-up old baseball. Beat-up old balls were all we’d ever had any- how. They were all we’d ever needed. The dirtier they were, and the more frayed the skin and stitching, the loud- er they’d hissed and the better they’d curved. And remembering this-re- covering in an instant the knowledge of how little we’d needed in order to be happy-my grief for my brother became palpable, took on shape and weight, color and texture, even an odor. The measure of my loss was pre- cisely the difference between one of the beat-up, earth-colored, grass-scent- ed balls that had given us such hap- piness and this antiseptic-smelling, sad-making, icon-ball on its bandage- box pedestal. And as I felt this-as I stood there palpating my grief, shifting it around like a throwing stone in my hand-I fell through some kind of floor inside myself, landing in a deeper, brighter chamber just in time to feel something or someone tell me: But who’s to say we need even an old baIl to be happy? Who’s to say we couldn’t do with less?Who’s to say we couldn’t still be happy-with no ball at all?

And with that, the koan was solved.

I can’t explain why this felt like such a complete solution. Reading the bare words, two decades later, they don’t look like much of a solution. But a koan answer is not a verbal, or a literary, or even a personal experience: It’s a spiritual experience. And a boy, a man, a “me,” does not have spiritual experiences; only the spirit has spiritual experiences. That’s why churches so soon become bandage boxes propping up antiseptic icons that lose all value the instant they are removed from the greens and browns of grass and dirt and life. It’s also why a good Zen monk always states a koan solution in the barest possible terms. “No ball at all!” is, perhaps, all I should have written-because then no one would have an inkling of what was meant and so could form no misconceptions, and the immediacy and integrity and authority of the experience would be safely locked away.

This is getting a bit iffy for a sports story. But jocks die, and then what? The brother I played a thousand games of catch with is dead, and so will I be, and unless you’re one hell of an athlete so will you be. In the face of this fact, I find it more than a little con- soling to recall how clearly and deeply it was brought home to me, that October day, that there is something in us which needs absolutely nothing- not even a dog-eared ball-in order to be happy. From that day forward the relic on the mantel lost its irksome overtones and became a mere auto- graphed ball-nothing more, nothing less. It lives on my desk now, beside an old beater ball my brother and I wore out, and it gives me a satisfaction I can’t explain to sit back, now and then, and compare the two-though I’d still gladly trash the white one for a good game of catch.

As for the ticklish timing of its arrival, I only recently learned a couple of facts that shed some light. First, I discovered–in a copy of the old letter my mother wrote to Mantle- that she’d made it quite clear that my brother was dying. So when The Mick wrote what he wrote, he knew perfectly well what the situation might be when the ball arrived. And second, I found out that my mother actually went ahead and showed the ball to my brother. True, what was – left of him was embalmed. But what was embalmed wasn’t all of him. And I’ve no reason to assume that the un- embalmed part had changed much. It should be remembered, then, that while he lived my brother was more than a little vain, that he’d been compelled by his death to leave a handsome head of auburn hair be- hind, and that when my mother and the baseball arrived at the funeral parlor, that lovely hair was being prepared for an open-casket funeral by a couple of cadaverous-looking yahoos whose oily manners, hair, and clothes made it plain that they didn’t know Kookie from Roger Maris or Solid Cool from Kool-Aid. What if this pair took it into their heads to spruce John up for the hereafter with a Bible camp cut? Worse yet, what if they tried to show what sensitive, accommodating artists they were and decked him out like a damned Elvis the Pelvis greaser? I’m not trying to be morbid here. I’m just trying to state the facts. “The Bod” my brother had very much enjoyed inhabiting was about to be seen for the last time by all his buddies, his family, and a girl- friend who was only 1.5 percent Crud, and the part of the whole ensemble he’d been most fastidious about-the coiffure-was completely out of his control! He needed best wishes. He needed a pal. Preferably one with a comb.

Enter my stalwart mother, who took one look at what the two rouge-and- casket wallahs were doing to the hair, said, “No, no, no!”, produced a snap- shot, told them, “He wants it exactly like this,” sat down to critique their efforts, and kept on critiquing until in the end you’d have thought John had dropped in to groom himself.

Only then did she ask them to leave. Only then did she pull the autographed ball from her purse, share it with her son, read him the inscription.

As is always the case with arriving baseballs, timing is the key. Thanks to the timing that has made The Mick a legend, my brother, the last time we all saw him, looked completely himself.

I return those best wishes to my brother’s pal.