is a semi-autobiographical novel written by Ernest Hemingway concerning events during the Italian campaigns during the World War I. The book, published in 1929, is a first-person account of American Frederic Henry, serving as a Lieutenant (“Tenente”) in the ambulance corps of the Italian Army. The title is taken from a poem by 16th-century English dramatist George Peele.

is a semi-autobiographical novel written by Ernest Hemingway concerning events during the Italian campaigns during the World War I. The book, published in 1929, is a first-person account of American Frederic Henry, serving as a Lieutenant (“Tenente”) in the ambulance corps of the Italian Army. The title is taken from a poem by 16th-century English dramatist George Peele.

A Farewell to Arms focuses on a doomed romance between Henry and a British nurse, Catherine Barkley, against the backdrop of the First World War, cynical soldiers, fighting and the displacement of populations. Although this was Hemingway’s bleakest novel, its publication cemented his stature as a modern American writer.

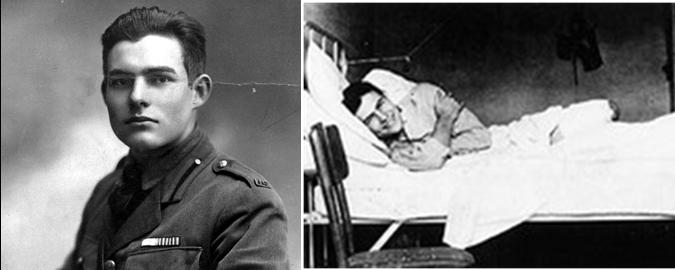

Ernest Hemingway served in World War I in the Red Cross Ambulance Corps. At the age of 18, in June, 1918, he arrived in Europe and was wounded on July 8. He spent nine months recuperating in Milan, sitting in cafes and bars and falling in love with his nurse, Agnes von Kurowski.  After the war, he moved to Paris where he began writing A Farewell to Arms. He did not finish the novel there, but continued writing it as he traveled in America in 1928 and 1929. Many of Hemingway’s own experiences in the war are reflected in the novel. Many of the characters are also based on real people Hemingway met and knew during his time in Italy and France. When the novel was published, it helped cement Hemingway’s reputation as one of America’s greatest young writers.

After the war, he moved to Paris where he began writing A Farewell to Arms. He did not finish the novel there, but continued writing it as he traveled in America in 1928 and 1929. Many of Hemingway’s own experiences in the war are reflected in the novel. Many of the characters are also based on real people Hemingway met and knew during his time in Italy and France. When the novel was published, it helped cement Hemingway’s reputation as one of America’s greatest young writers.

A Farewell to Arms Writing Style

Ordered Chaos

You’ve probably heard about Ernest Hemingway’s “Iceberg Principle” or theory of omission. It’s the simple idea that the reader is to be trusted. All the reader needs is the surface information (the part of the iceberg we can see) to understand the situations being discussed (or the water below the visible iceberg). Whether it’s a world at war or the battles raging within human minds, the situations in A Farewell to Arms are chaotic. By presenting a very ordered surface for the reader, the reader is able to examine the chaos and complexity with a fairly clear head. Here’s an example:

Well, we were in it. Every one was caught in it and the small rain would not quiet it. “Good-night, Catherine,” I said out loud. “I hope you sleep well. If it’s too uncomfortable, darling, lie on the other side,” I said. “I’ll get you some cold water. In a little while it will be morning and then it won’t be so bad. I’m sorry he makes you so uncomfortable. Try and go to sleep, sweet.”

I was asleep all the time, she said. You’ve been talking in your sleep (28.24).

All the chaos is right there. The loneliness and despair of Frederic and the other men, the deep love he shares with Catherine, the pain of being apart from her, his worry for her pregnancy, his resentment of the baby, his belief that he and Catherine have a psychic connection, and so much more, in three ordered paragraphs. Nobody has to tell us that Frederic is dreaming. Just like when Catherine is prepping Frederic for surgery, and she says, “There darling. Now you’re all clean inside and out” (16.56). We know she’s just given him an enema, and that her words there imply that Catherine thinks Frederic has undergone a rite of purification.

This is what Modernism is all about, creating a form, in this case a very ordered one (for a more chaotic form of Modernism see F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night.) to represent the chaos of the times.