Victor Hugo’s poetry is praised as highly as, if not higher than, his prose by the French; however, finding translations of his poetry in English is a challenge. All English translations used to be out of print. In April 2001, this changed with the publication of a new translation of selected poems (“Selected Poems of Victor Hugo: A Bilingual Edition” Translated by EH and AM Blackmore. University of Chicago Press. )

The poems of Victor Hugo captured the spirit of the Romantic era. They were largely devoted to 19th century causes. Many touched on religious themes. Initially they were royalist but soon became Bonapartist, Republican, and liberal. Hugo’s poems on nature revealed a continuing search for the great sublime (elevate to a high degree of moral or spiritual purity or excellence).

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by François-René de Chateaubriand, the founder of Romanticism and France’s preeminent literary figure during the early 1800s. In his youth, Hugo resolved to be “Chateaubriand or nothing,” and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor’s in many ways. Like Chateaubriand, Hugo would further the cause of Romanticism, become involved in politics as a champion of Republicanism, and be forced into exile due to his political stances. Between 1829 and 1840 he would publish five more volumes of poetry (Les Orientales, 1829; Les Feuilles d’automne, 1831; Les Chants du crépuscule, 1835; Les Voix intérieures, 1837; and Les Rayons et les ombres, 1840), cementing his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time.

The passion and eloquence of Hugo’s early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry (Nouvelles Odes et Poésies Diverses) was published in 1824, when Hugo was only twenty two years old, and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, it was the collection that followed two years later in 1826 (Odes et Ballades) which revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song.

Read the following poems and be prepared to discuss the merit of Hugo’s poetry. What appear to be common themes? How does Hugo use rhythm, form and figurative expression to influence the quality of his work? Select two poems that you will use to demonstrate your observation of rhythm, form and figurative. Submit your notes to Turnitin.

THE GENESIS OF BUTTERFLIES

by: Victor Hugo (1802-1885)

HE dawn is smiling on the dew that covers

HE dawn is smiling on the dew that covers- The tearful roses; lo, the little lovers

- That kiss the buds, and all the flutterings

- In jasmine bloom, and privet, of white wings,

- That go and come, and fly, and peep and hide,

- With muffled music, murmured far and wide.

- Ah, the Spring time, when we think of all the lays

- That dreamy lovers send to dreamy mays,

- Of the fond hearts within a billet bound,

- Of all the soft silk paper that pens wound,

- The messages of love that mortals write

- Filled with intoxication of delight,

- Written in April and before the May time

- Shredded and flown, playthings for the wind’s playtime,

- We dream that all white butterflies above,

- Who seek through clouds or waters souls to love,

- And leave their lady mistress in despair,

- To flit to flowers, as kinder and more fair,

- Are but torn love-letters, that through the skies

- Flutter, and float, and change to butterflies.

This English translation of “The Genesis of Butterflies” was composed by Andrew Lang (1844-1912).

THE GRAVE AND THE ROSE

THE Grave said to the Rose,

“What of the dews of dawn,

Love’s flower, what end is theirs?”

“And what of spirits flown,

The souls whereon doth close

The tomb’s mouth unawares?”

The Rose said to the Grave.

The Rose said, “In the shade

From the dawn’s tears is made

A perfume faint and strange,

Amber and honey sweet.”

“And all the spirits fleet

Do suffer a sky-change,

More strangely than the dew,

To God’s own angels new,”

The Grave said to the Rose.

This English translation of “The Grave and the Rose” was composed by Andrew Lang (1844-1912).

MORE STRONG THAN TIME

SINCE I have set my lips to your full cup, my sweet,

Since I my pallid face between your hands have laid,

Since I have known your soul, and all the bloom of it,

And all the perfume rare, now buried in the shade;

Since it was given to me to hear on happy while,

The words wherein your heart spoke all its mysteries,

Since I have seen you weep, and since I have seen you smile,

Your lips upon my lips, and your eyes upon my eyes;

Since I have known above my forehead glance and gleam,

A ray, a single ray, of your star, veiled always,

Since I have felt the fall, upon my lifetime’s stream,

Of one rose petal plucked from the roses of your days;

I now am bold to say to the swift changing hours,

Pass, pass upon your way, for I grow never old,

Fleet to the dark abysm with all your fading flowers,

One rose that none may pluck, within my heart I hold.

Your flying wings may smite, but they can never spill

The cup fulfilled of love, from which my lips are wet;

My heart has far more fire than you can frost to chill,

My soul more love than you can make my soul forget.

This English translation of “More Strong than Time” was composed by Andrew Lang (1844-1912).

THE OCEAN’S SONG

WE walked amongst the ruins famed in story

Of Rozel-Tower,

And saw the boundless waters stretch in glory

And heave in power.

O Ocean vast! We heard thy song with wonder,

Whilst waves marked time.

“Appear, O Truth!” thou sang’st with tone of thunder,

“And shine sublime!

“The world’s enslaved and hunted down by beagles,

To despots sold.

Souls of deep thinkers, soar like mighty eagles!

The Right uphold.

“Be born! arise! o’er the earth and wild waves bounding,

Peoples and suns!

Let darkness vanish; tocsins be resounding,

And flash, ye guns!

“And you who love no pomps of fog or glamour,

Who fear no shocks,

Brave foam and lightning, hurricane and clamour,–

Exiles: the rocks!”

This English translation of “The Ocean’s Song” was composed by Toru Dutt (1856-1877).

THE POOR CHILDREN

TAKE heed of this small child of earth;

He is great; he hath in him God most high.

Children before their fleshly birth

Are lights alive in the blue sky.

In our light bitter world of wrong

They come; God gives us them awhile.

His speech is in their stammering tongue,

And his forgiveness in their smile.

Their sweet light rests upon our eyes.

Alas! their right to joy is plain.

If they are hungry Paradise

Weeps, and, if cold, Heaven thrills with pain.

The want that saps their sinless flower

Speaks judgment on sin’s ministers.

Man holds an angel in his power.

Ah! deep in Heaven what thunder stirs,

When God seeks out these tender things

Whom in the shadow where we sleep

He sends us clothed about with wings,

And finds them ragged babes that weep!

This English translation of “The Poor Children” was composed by Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909).

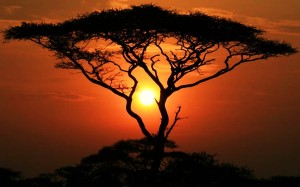

A SUNSET (From “Feuilles d’Automne”)

I LOVE the evenings, passionless and fair, I love the evens,

Whether old manor-fronts their ray with golden fulgence leavens,

In numerous leafage bosomed close;

Whether the mist in reefs of fire extend its reaches sheer,

Or a hundred sunbeams splinter in an azure atmosphere

On cloudy archipelagos.

Oh, gaze ye on the firmament! a hundred clouds in motion,

Up-piled in the immense sublime beneath the winds’ commotion,

Their unimagined shapes accord:

Under their waves at intervals flame a pale levin through,

As if some giant of the air amid the vapors drew

A sudden elemental sword.

The sun at bay with splendid thrusts still keeps the sullen fold;

And momently at distance sets, as a cupola of gold,

The thatched roof of a cot a-glance;

Or on the blurred horizon joins his battle with the haze;

Or pools the blooming fields about with inter-isolate blaze,

Great moveless meres of radiance.

Then mark you how there hangs athwart the firmament’s swept track,

Yonder a mighty crocodile with vast irradiant back,

A triple row of pointed teeth?

Under its burnished belly slips a ray of eventide,

The flickerings of a hundred glowing clouds in tenebrous side

With scales of golden mail ensheathe.

Then mounts a palace, then the air vibrates–the vision flees.

Confounded to its base, the fearful cloudy edifice

Ruins immense in mounded wrack;

Afar the fragments strew the sky, and each envermeiled cone

Hangeth, peak downward, overhead, like mountains overthrown

When the earthquake heaves its hugy back.

These vapors, with their leaden, golden, iron, bronzèd glows,

Where the hurricane, the waterspout, thunder, and hell repose,

Muttering hoarse dreams of destined harms,–

‘Tis God who hangs their multitude amid the skiey deep,

As a warrior that suspendeth from the roof-tree of his keep

His dreadful and resounding arms!

All vanishes! The Sun, from topmost heaven precipitated,

Like a globe of iron which is tossed back fiery red

Into the furnace stirred to fume,

Shocking the cloudy surges, plashed from its impetuous ire,

Even to the zenith spattereth in a flecking scud of fire

The vaporous and inflamèd spaume.

O contemplate the heavens! Whenas the vein-drawn day dies pale,

In every season, every place, gaze through their every veil?

With love that has not speech for need!

Beneath their solemn beauty is a mystery infinite:

If winter hue them like a pall, or if the summer night

Fantasy them starre brede.

This English translation of “A Sunset” was composed by Francis Thompson (1859-1907).

1er janvier

Enfant, on vous dira plus tard que le grand-père

Vous adorait; qu’il fit de son mieux sur la terre,

Qu’il eut fort peu de joie et beaucoup d’envieux,

Qu’au temps où vous étiez petits il était vieux,

Qu’il n’avait pas de mots bourrus ni d’airs moroses,

Et qu’il vous a quittés dans la saison des roses;

Qu’il est mort, que c’était un bonhomme clément;

Que, dans l’hiver fameux du grand bombardement,

Il traversait Paris tragique et plein d’épées,

Pour vous porter des tas de jouets, des poupées,

Et des pantins faisant mille gestes bouffons;

Et vous serez pensifs sous les arbres profonds.

The First of January

Child, lets speak of your Grand Father later

The one you loved, the one who loved life.

And had a joyous disposition that knew no boundaries.

When you were young he was already old.

He neither spoke nor acted morosely,

And passed during the season of roses.

He traversed Paris for you through,

A city full of swords and tragedy,

Braving the famous bombardment

To bring you an abundance toys, dolls,

And puppets with a thousand silly faces.

Left you deep in reflection under the trees.